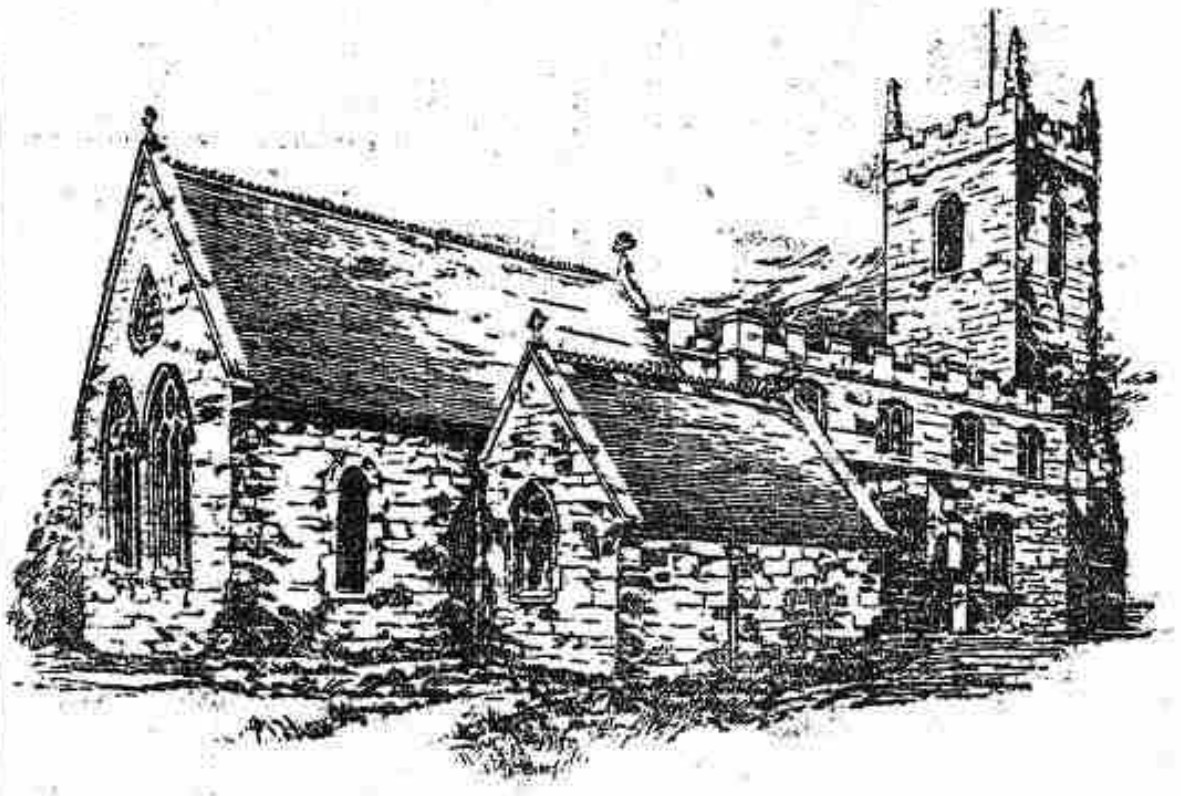

For the first documented organ, we have to wait until the restoration of the church in 1871, when a vestry was erected on the north side. The middle north lancet window was converted into a doorway into the vestry, while the westernmost lancet was made into an arch for the organ chamber1 into which was placed a small organ, which was bought from Sneinton Church for £44 on 1st March 1871.2 It was reported that, at the opening service, Mr Gunn “caused it to be heard to advantage” and “it was a sweet toned instrument”.

For the first documented organ, we have to wait until the restoration of the church in 1871, when a vestry was erected on the north side. The middle north lancet window was converted into a doorway into the vestry, while the westernmost lancet was made into an arch for the organ chamber1 into which was placed a small organ, which was bought from Sneinton Church for £44 on 1st March 1871.2 It was reported that, at the opening service, Mr Gunn “caused it to be heard to advantage” and “it was a sweet toned instrument”.

Mr Gunn had been choir master at St Giles’ for several years3 and now added organist to his duties. At the 1873 harvest festival it was reported that: “Mr Gunn may be congratulated on the excellent taste he displayed in playing the organ, and the admirable training he had given to the choir”.4 Then, in the following year, “the services on Christmas day were fully choral, rendered admirably by the choir. The musical portion was by Mr George Gunn, the organist, who, we are sure, must have used every exertion to have made his part of the service worthy of the glorious day”.5

Mr Gunn had been choir master at St Giles’ for several years3 and now added organist to his duties. At the 1873 harvest festival it was reported that: “Mr Gunn may be congratulated on the excellent taste he displayed in playing the organ, and the admirable training he had given to the choir”.4 Then, in the following year, “the services on Christmas day were fully choral, rendered admirably by the choir. The musical portion was by Mr George Gunn, the organist, who, we are sure, must have used every exertion to have made his part of the service worthy of the glorious day”.5

Mr Gunn was a young man, in his twenties, who was a clerk in Heymann and Alexander’s lace business.6 He died in 1875, at the age of only twenty-nine, leaving a widow who at his death was pregnant with their second child.

All that is known of the organists for the next twenty years is that Mr William Stevenson, a local school teacher7, was organist from at least 18848 until 18929.

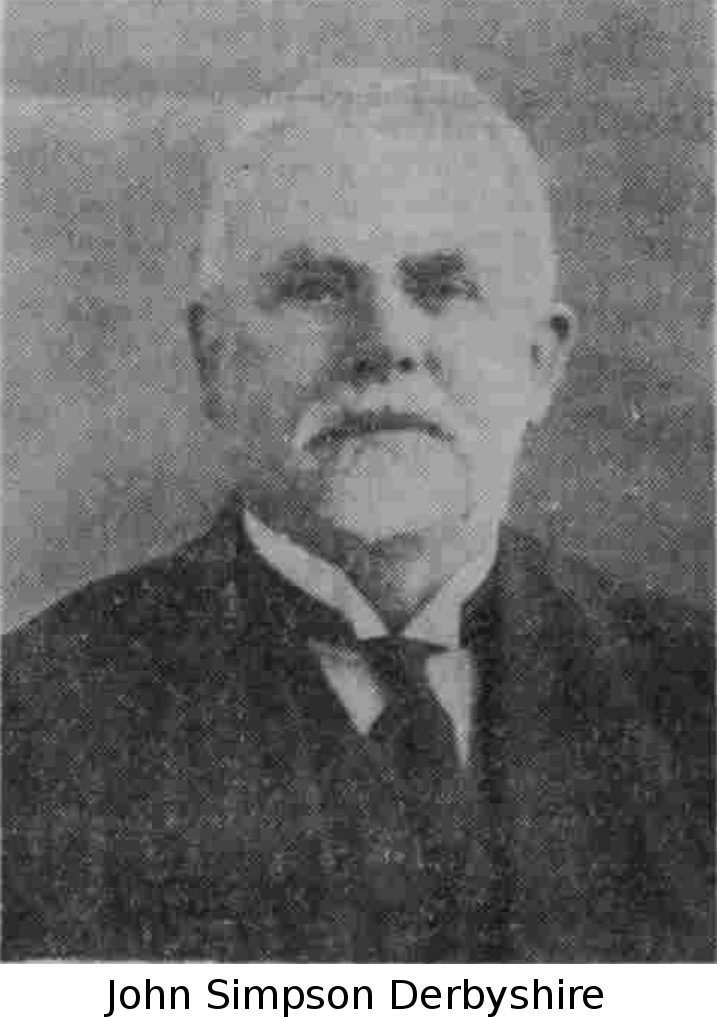

At the time of the bazaar held in 1895 to raise funds for the extension of the church, Miss Pemberton was listed as church organist with Mr W E Bass as honorary choirmaster.10 Under the heading of the Church Extension Services Council, there was also listed: hon. organist Mrs Hector Tomkins; dep. hon. organist Mr A Drake; hon. choirmaster Mr J S Derbyshire; dep. hon. choirmaster Mr W Roescher; and hon. choirmaster for boys’ practice Mr Garner. Furthermore, under the heading of the Children’s Services’ Committee were listed hon. organist Miss M Robinson and hon. choirmasters Messrs A D Fisher and E Haylock.

As the congregation outgrew the church accommodation, services were eventually also held at the newly-built Board School and the National Schoolroom.11 Hence the need for extra choirs with choirmasters and organists. An additional organ was bought and Mr Derbyshire was thanked for the trouble he took in purchasing “the best organ for the least money”12 with the organ being put in order at the Board School in the middle of 1896.13

A boy was employed as organ blower. This may have been an ad hoc arrangement at first as he is recorded as receiving a Christmas box of 5/- at the end of 1895, but in June 1896 Miss Pemberton was authorised to engage an organ blower at 20/- a year. This sum evidently proved insufficient as in the following month it was agreed that “the organ blower be paid 20/- to date and 1/- per week afterward”.14

It was Mrs Tomkins, rather than Miss Pemberton, who played the organ at the service to lay the foundation stone for the church extension on 28th October 1896. The previous month, Miss Florence Ackroyd Pemberton had married Mr Francis Parker Kirk, an amateur singer with “an excellent bass-baritone voice” who was a frequent contributor to local concert programmes.15 Although her absence at the organ for the extension service may not have been related to her marriage, her decision to retire as church organist at the end of the year certainly was: Mrs Kirk was expecting their first child. Mrs Tomkins was then offered the position of organist: she accepted and gave her services for free, declining the offered salary of £15 per year.16

The question arose of what to do with the organ in the church while the building work took place. Initially, it was advertised for sale at £25 in Exchange & Mart. But it was then decided to ask Messrs Lloyd and Co to give a price for taking down, storing and refixing the organ in good condition after the new church had been completed. A later offer of £12 for the organ was declined.17

Eventually, however, the choir committee decided that they would like to have a new organ for the newly extended church and, having obtained the support of the church council,18 in due course placed a contract with Lloyd’s for £300 to build a new organ.19

Mr James Buckland Lyddon was appointed organist in October 1898 at £20 per year, with Mrs Tomkins as assistant choirmaster on the same salary.20 Mr Bass resigned as choirmaster a month or so later after “holding the position in a most satisfactory manner for five years”.21 William Ernest Bass had been in partnership with Charles Gill as lace manufacturers, but retired from the partnership on 1st December.22 Mr Derbyshire was appointed choirmaster in his place.

Mr James Buckland Lyddon was appointed organist in October 1898 at £20 per year, with Mrs Tomkins as assistant choirmaster on the same salary.20 Mr Bass resigned as choirmaster a month or so later after “holding the position in a most satisfactory manner for five years”.21 William Ernest Bass had been in partnership with Charles Gill as lace manufacturers, but retired from the partnership on 1st December.22 Mr Derbyshire was appointed choirmaster in his place.

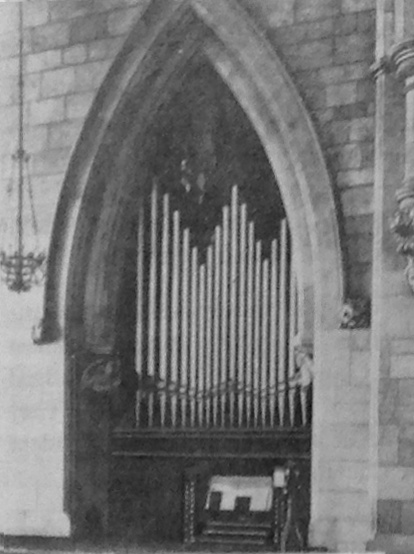

![]() The old church organ was given to Lady Bay Church at the end of 189823 and the temporary organ was advertised for sale at the end of 1899.24

The old church organ was given to Lady Bay Church at the end of 189823 and the temporary organ was advertised for sale at the end of 1899.24

The report of the dedication of the new organ on 22nd November 1899 included a detailed description of the organ:25

“A service of special character was held at West Bridgford Parish Church on Wednesday to dedicate the new organ, which has been built in the south transept at a cost of about £500, by Messrs C Lloyd and Co. of Nottingham. Formerly the choir were led by a large American organ, but now the church possesses a magnificent instrument, embracing all the most modern improvements.

“When completed, the organ will be three manual, but at present only two have been fitted with stops, an additional £300 being required to finish the work. The stops on the great organ are 8ft clarabells, open diapason, and keraulophon, 4ft principal, and 2ft fifteenth, while the swell contains 16ft bourdon, 8ft open diapason, salicional, voix celeste, and opol, 4ft gemshorn, and 2ft fifteenth, with 16ft bourdon pedals, and the usual couplers, and College of Organists’ pedal board.

“Although at present situate in the south transept, the organ will ultimately be removed to the north transept when the necessary accommodation can be made. The fine qualities of the organ were fully tested by Mr J B Lyddon, who performed Lemmens’ triumphal march, a pastorale in B minor by Guilmant, and Batiste’s Offertoire in E. There was a large congregation.”

The console for the organ was placed on the south side of the new chancel. As part of the work on the church extension, the ancient wooden screen had been moved eastwards, converting the old chancel into a recess in which the organ itself was housed. The organ was hidden from the congregation by a curtain behind the wooden screen and, in September 1900, Mr Simons offered to put up some dummy pipes to cover the woodwork of the organ which could still be seen.26

The console for the organ was placed on the south side of the new chancel. As part of the work on the church extension, the ancient wooden screen had been moved eastwards, converting the old chancel into a recess in which the organ itself was housed. The organ was hidden from the congregation by a curtain behind the wooden screen and, in September 1900, Mr Simons offered to put up some dummy pipes to cover the woodwork of the organ which could still be seen.26

By 1902, the organ committee was keen to enlarge the organ with extra stops. Indeed, the organist, Mr Lyddon, even offered to contribute a year’s salary by way of support. The church council responded by agreeing that up to £100 could be spent by the committee on enlarging the organ.27 Fund raising continued for some time, with collections from services in September 1903 also being allocated to the organ fund.28

The Church Council meeting on 31st March 1903 was a stormy one. The issue of organists being one of the more minor items, but resulted in Mr Tomkins making clear his views on the Rector’s actions: “Mr Tomkins then questioned the Rector as to an advertisement in Church Times for organist to take weekday services and train boys and, on the Rector admitting that it referred to Mr & Mrs Tomkins, spoke a few straight words. The Rector’s action was condemned by the Council.”29 The Rector resigned a few days later.

In the middle of 1904, Mr Lyddon resigned and the Rector announced that Mr W Ryde had been appointed as organist.30 However, Mr Ryde decided not to come. Instead, Mr Vernon Read took up the appointment on 2nd October, although his time at St Giles’ was to prove to be short.31 The Council Meeting of 6th February found itself giving a “very hearty vote of appreciation and thanks to Mr J S Derbyshire for the valued service he had rendered to the Church for a goodly period as honorary choirmaster”. At the same time, Vernon Read stood down as organist and the parish magazine recorded “appreciation of Mr Read’s services during the months he had been connected with us”.

Mr Derbyshire was a very successful amateur conductor, working with choirs such as the Nottingham Tonic Sol-fa Choral Society and the West Bridgford Glee Club.32 Although he remained a keen musician all his life, conducting a performance of The Messiah just a couple of months before he died at the age of 77, Mr Derbyshire stepped down from his position at St Giles’ because of the increasing demands of the wholesale grocers and manufacturing confectioners that he had founded some years earlier.33

Mr Derbyshire was a very successful amateur conductor, working with choirs such as the Nottingham Tonic Sol-fa Choral Society and the West Bridgford Glee Club.32 Although he remained a keen musician all his life, conducting a performance of The Messiah just a couple of months before he died at the age of 77, Mr Derbyshire stepped down from his position at St Giles’ because of the increasing demands of the wholesale grocers and manufacturing confectioners that he had founded some years earlier.33

Vernon Sydney Read was a professional musician whose career subsequently included being organist at St Mary’s Nottingham from 1922 to 1928, and then at St John’s, Torquay until 1947.34

St Giles’ acted quickly in re-appointing Mr James Buckland Lyddon into the joint position of Organist and Choirmaster, with Mr and Mrs Tomkins continuing as deputies.35 Mr Lyddon had a business in Nottingham as a lace manufacturer. Coming home from a business trip to Scotland in December 1907, he was suddenly struck-down with pneumonia and died, aged only 42.36

By February 1908, Mr William Ryde had been appointed as organist and choirmaster.37 Like Mr Lyddon, he had previously been organist and choirmaster at St James’s and was in great demand in the area as an accompanist on the piano.38 It is not known exactly when Mr Ryde relinquished his duties at St Giles’. In Wright’s Directory for 1910-11 he is listed in the rôle but the directory for 1913-14 has Mr Hector Tomkins as choirmaster, with his wife as organist,

Mr Tomkins was headmaster of Sneinton Boulevard Senior School in Nottingham, a post which he was to hold for over forty years.39 He also had a long association with St Giles’ where, in 1950 at the age of 92, he was said to be still a member of the church choir.40 He had married Cicely Crisp, whose father was a piano maker, in 1885.

In 1912, it was announced that “the organ is to be enlarged and removed to a new position at a cost of some £400 or £500”.41

With the completion of the north aisle in 1919, the organ was moved to the new north chapel where it stood “almost completely hidden and set back more than twelve feet into the choir vestry”.42

With the completion of the north aisle in 1919, the organ was moved to the new north chapel where it stood “almost completely hidden and set back more than twelve feet into the choir vestry”.42

Mr and Mrs Tomkins resigned in July 192043 and Mr Charles Bissill Morris became organist and choirmaster.44,45 By this time, Mr Morris was running the draper’s shop in Hockley that had been established by his father and was known as James Morris & Son, but he brought with him 30 years of experience as a church organist.

Mr and Mrs Tomkins resigned in July 192043 and Mr Charles Bissill Morris became organist and choirmaster.44,45 By this time, Mr Morris was running the draper’s shop in Hockley that had been established by his father and was known as James Morris & Son, but he brought with him 30 years of experience as a church organist.

In 1924 (although one report refers to Mr Morris as organist in February 192546) a young man, George Dudley Newball, became organist. Mr Newball worked at the Midland Bank in Daybrook.47 He was to remain in the post until he died in 1941, after a long illness, at the age of just 37.48

Mr Newball’s successor, Mr John Gordon Wood, was appointed in November 1941. He was an experienced organist and choirmaster: in 1913, at the age of 15, he had been appointed organist at St Philip’s in Nottingham and was appointed their choirmaster in the following year. He had held the same positions at St Stephen’s, Hyson Green, and at St Matthew’s.49 However, he did not pursue a career as professional musician but became an insurance broker.50

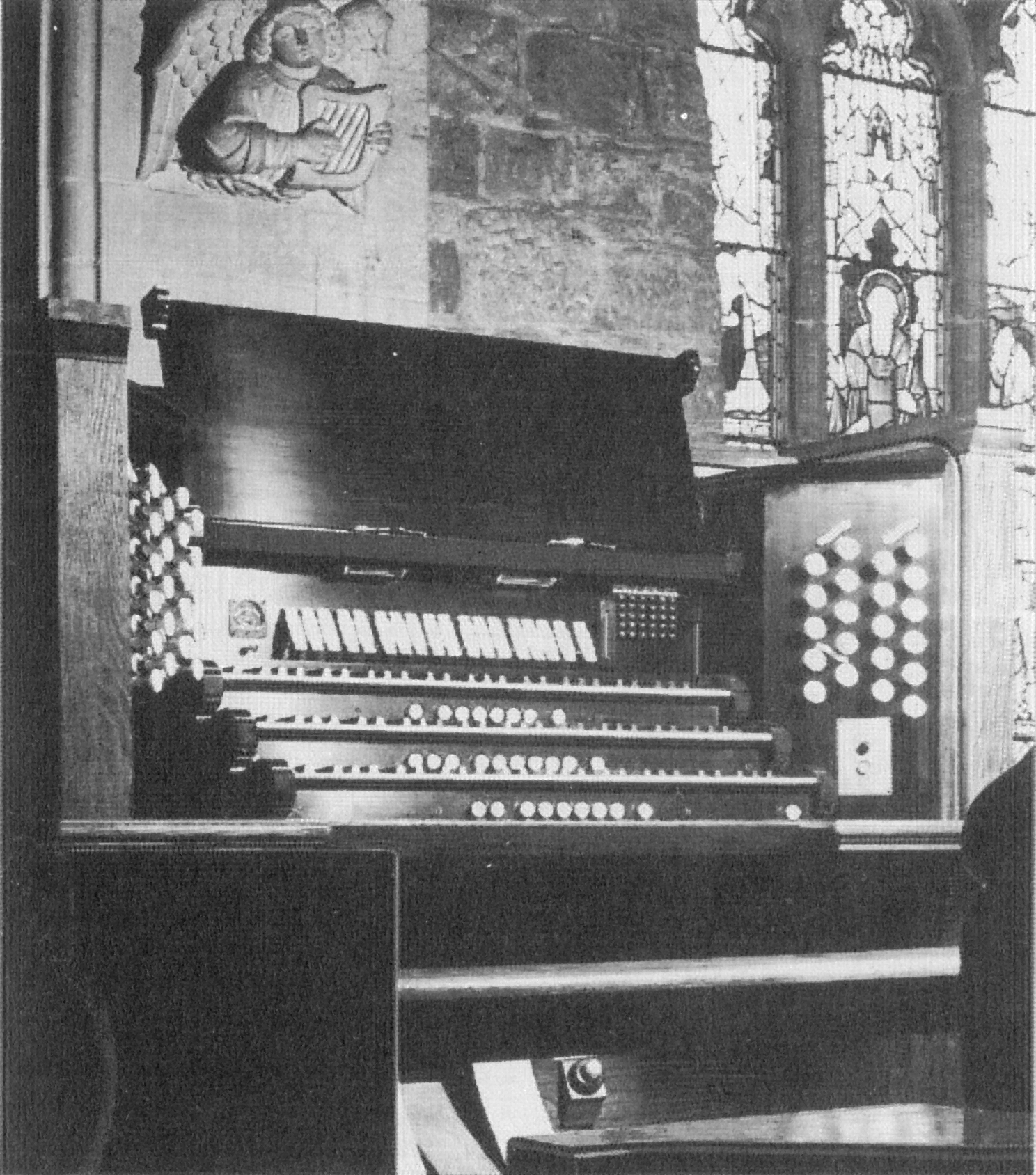

By 1936, it was decided that a new organ was needed and an appeal to raise the necessary £2,500 was launched.51 However, this was unsuccessful. A report in 1949 declared that the organ “needs completely rebuilding and a fund has been started for this purpose”52 but the organ which had had to withstand over 50 years of continuous use, and suffer the indignities of four floods53, had to wait a little longer before a successful appeal to rebuild and extend the organ was launched in February 1951.54 The sum of £4,100 was needed to rebuild and enlarge the great, swell and pedal organs, with a new choir organ for £1,700 and a third manual for £500. The work was carried out by Messrs Henry Willis and Sons Ltd and the re-built and enlarged organ was dedicated on 28th February 1952, with an opening recital in the following week by J Dykes Bower.55

The detached organ console was moved to the choir stalls on the south side of the chancel. The enlargement of the organ resulted in the pipework for the great and swell organs reaching out seven feet from the north wall of the church, intruding into the chapel. The organ blower was also placed in the choir vestry, together with a pipe leading to a window.56 Traces of this arrangement can still (2105) be seen in the choir vestry, for example the green glass used in the east window to fill the inlet of the blower pipe

The detached organ console was moved to the choir stalls on the south side of the chancel. The enlargement of the organ resulted in the pipework for the great and swell organs reaching out seven feet from the north wall of the church, intruding into the chapel. The organ blower was also placed in the choir vestry, together with a pipe leading to a window.56 Traces of this arrangement can still (2105) be seen in the choir vestry, for example the green glass used in the east window to fill the inlet of the blower pipe

During the rebuilding of the organ, an orchestra was formed to accompany the family service. In an article on church orchestras in 1963, The Times commented:57

“The most notable use of an orchestra in church is at St Giles West Bridgford, where in 1951 it was found necessary to rebuild the organ. A group of young players from the Nottingham Junior Harmonic Orchestra, four violins, four violas, and four cellos, offered to fill the breach and they were so well liked that they were asked to continue, once a month, after the organ was in use again.”

Mr Percival M Leeds, who conducted the Nottingham Junior Harmonic Orchestra, had been asked to provide this ‘church orchestra’, whose members sat in front of the pews either side of the main aisle. When the organ was in use again, the orchestra had been so well liked that Mr Leeds was asked to continue to provide an orchestra for the family service each week. This continued over the next 25 years with various different combinations of instrumentalists according to who was available. The original players were from the Nottingham Junior Harmonic Orchestra and West Bridgford Grammar School orchestra, but other interested musicians were welcomed. The orchestra later moved to the back of the church where there was more space.79

At the end of 1956, Mr Sidney Curtis gave a new oak music cabinet for the organ. It was designed to match the panels he had made some time previously, when the organ was rebuilt.58

Mr Gordon Wood resigned in June 1957 after fifteen years as organist. The parish magazine reported that he left “the choir as he would wish to, in good form with twenty boys and sixteen older members. They have won good opinions at Southwell and at our own church. There are many distractions today, but Mr Wood has trained half a generation of boys, often with very good results.”

Mr Wood’s successor as organist and choirmaster, later in 1957, was Mr Malcolm Courtenay Boyle who “is no stranger and has played for the services on a number of occasions, and conducted the practices. We are fortunate to find someone of his great musical ability available in our own parish, with all his experience of choirs and cathedral music at Windsor, Chester and Canterbury.”59 As well as having been an organist at Chester Cathedral, Mr Boyle was a composer60, and two of his anthems – ‘Thou, O God, art praised in Sion’ and ‘Daughters of Zion’ – together with ‘Four Love Lyrics’ are still available from the Paraclete Press.

It was not until 1958 that the organ was truly complete:61

“Everyone seems pleased with the new organ pipes which we have wanted for five years to complete the appearance of the organ. At the time none were available and it would have been very expensive to have them specially made. Tin is £750 a ton and other metals too.

“They are called display pipes and do not speak like other organ pipes but have to be made to look exactly like them and carefully graduated in size to look well. When you want something you can’t really afford, it is sometimes as well to look round and see what other people have got, which they may not want.

“So the Rector went looking around other churches, and eventually found 28 at Ruddington which were to be moved when a new side chapel was made. He assured the Vicar their church would look much better without them. Another 22 were found at Cinderhill. and again the Vicar was told their chancel would be greatly improved without them on the wall. Both churches accepted this good and free advice. The last five centre pipes, which are ten feet high, were found to be spare when the old organ from Broad Street was moved to the University Hall.

“Through the good offices of Dr W L Sumner we got those too, which completed our requirements. A fine organ deserves a fine case, and as we hear our own, played as it is to-day, all the cost and trouble seems very worth while. No longer shall we see the black cloth covering the mechanism, and the plain choir swell box, which was not intended to be seen at all. There is an enormous amount in any large organ which has to be put out of sight, much more than most people realise. All we see as a rule are some of the pipes of the large Diapason stop, but in our organ there are 2,000 altogether, in various places.”

However, not all was well with the organ. The problem was how it was positioned: the main organ pipes were on the north wall of the church, the choir organ pipes were on the other side of the north chapel close to the northernmost side of the choir seating, while the console was just behind the southernmost choir seating. A balanced sound at the organist’s seat was only achieved by playing the main organ louder, resulting in a loud, unbalanced sound for those sitting in the north aisle. In April 1956, one of the choir members “complained of the volume of sound from the organ and asked if a glass screen could be provided behind the ladies stall”.62 This was done the following year and “was found to improve the chancel, both from the noise of the organ and from draughts”.63 Whilst this may have improved matters for the choir it would appear that the congregation were less fortunate. A PCC minute in 1958 recorded a member asking “if anything could be done to lessen the organ blast suffered by the congregation in the north aisle, and suggested filling in the stonework”.

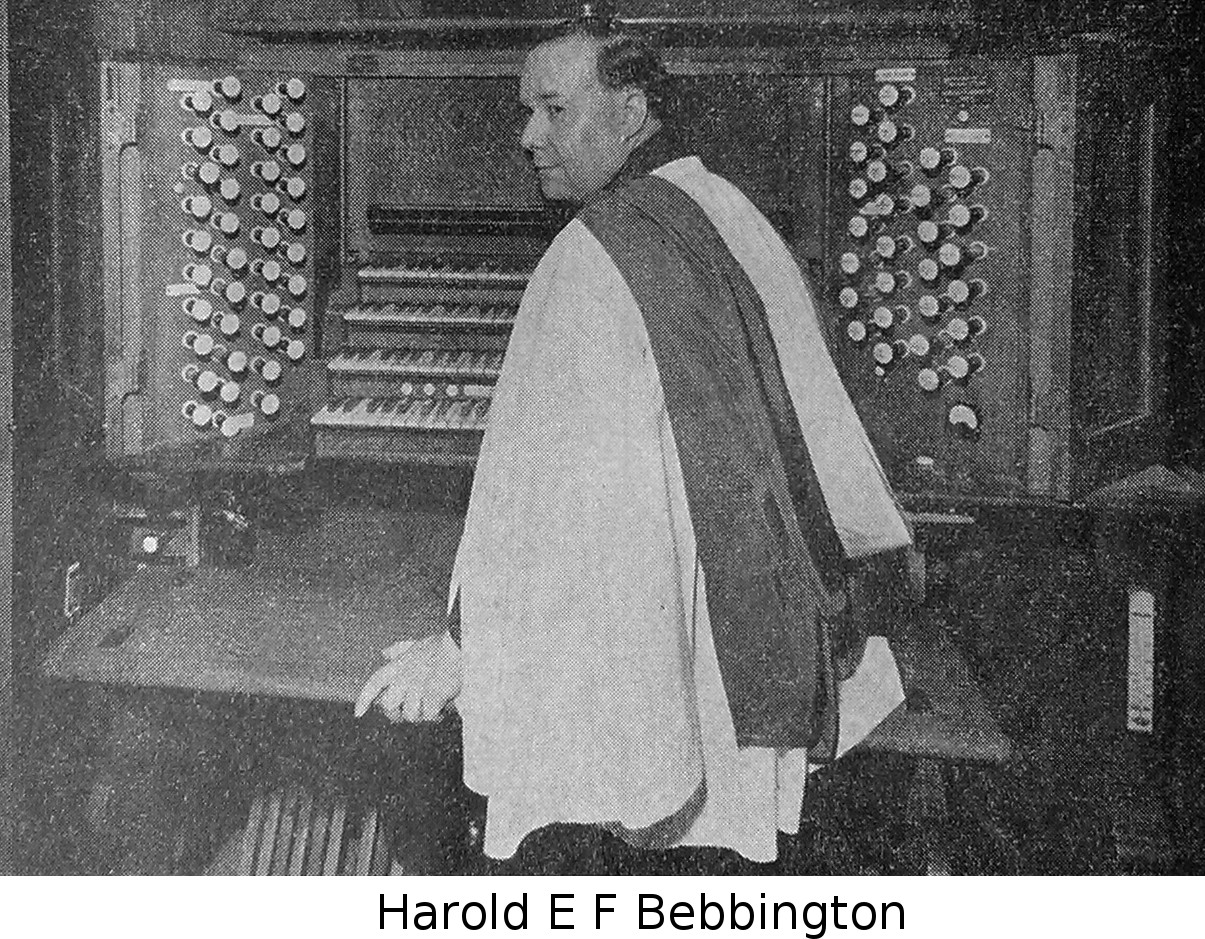

Mr Boyle left to return to Chester in 1961 and was succeeded, at the beginning of the following year, by Mr Harold Bebbington.64Mr Bebbington came to St Giles’ from St Andrew’s, Nottingham and was “an accomplished and well-qualified organist and choirmaster, with experience of various churches in Nottingham and also of broadcasting”. In June 1964 he gave a review of the choir’s progress since he had taken over:65

Mr Boyle left to return to Chester in 1961 and was succeeded, at the beginning of the following year, by Mr Harold Bebbington.64Mr Bebbington came to St Giles’ from St Andrew’s, Nottingham and was “an accomplished and well-qualified organist and choirmaster, with experience of various churches in Nottingham and also of broadcasting”. In June 1964 he gave a review of the choir’s progress since he had taken over:65

“There were 12 adult members when he came and eight now, though this represented a considerable turnover. The boys had been maintained at 18 to 20 with a turnover of 60 boys. We had learnt new responses, repaired the chanting considerably and had sung 28 anthems (including carols), had seven more nearly ready, were studying four and had three in our folders untouched as yet.”

Mr Bebbington later went on to teach in further education, including at Kingston-on-Thames College, before retiring back to Nottingham in the early 1980s. When he left, Mr Walter L Rogers became organist and choirmaster in November 1965.66 Mr Rogers had been Head of the Music Department at West Bridgford Grammar School for 14 years.

Mr Rogers embarked on enlarging the choir and in his review of 1967 reported that “great strides had been made during the year in recruitment. The general standard of the singing and improvement in the boys’ behaviour had been the subject of favourable comment.”67 Recruitment may have been assisted by the choir’s social activities: “The adults are proud of the record of our choir boys’ football club. The boys are so keen that it is sometimes a little difficult to switch their attention from football to singing!”68

Mr Rogers embarked on enlarging the choir and in his review of 1967 reported that “great strides had been made during the year in recruitment. The general standard of the singing and improvement in the boys’ behaviour had been the subject of favourable comment.”67 Recruitment may have been assisted by the choir’s social activities: “The adults are proud of the record of our choir boys’ football club. The boys are so keen that it is sometimes a little difficult to switch their attention from football to singing!”68

New recruits meant that more time had to be devoted to practice and at the annual general meeting of the choir in February 1970 “of the many subjects discussed the most important was ‘how to improve the quality of singing’. It was agreed that more rehearsal time was necessary, and it was decided to resume pre-service rehearsals and to begin Thursday rehearsals promptly at 7.15 pm.”

Mr Rogers left at the end of August 1970 and was replaced by Mr A Walter Esswood in the November.69

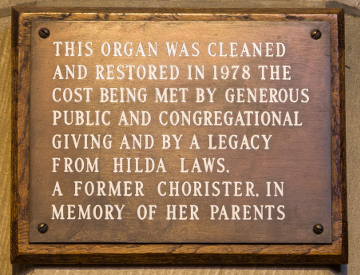

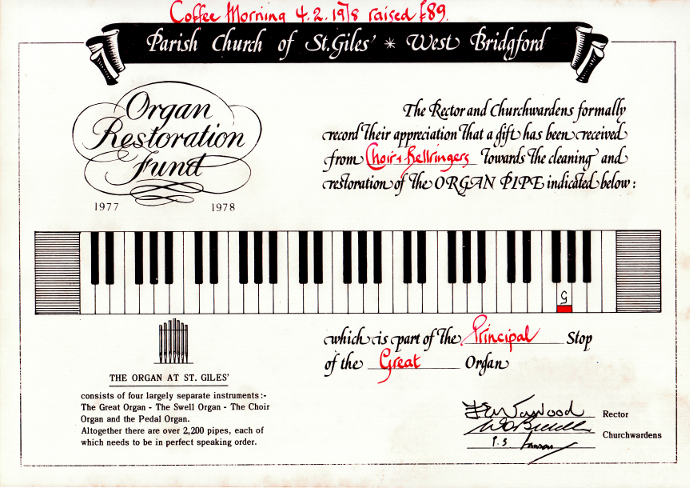

The organ was cleaned and restored in 1978.

The organ was cleaned and restored in 1978.

During Mr Esswood’s time, in October 1981, BBC’s ‘Songs of Praise’ was broadcast from St Giles’ with Mr Esswood as organist. When Mr Esswood left in November 198470, there was a gap of several months until Mr Fred Munday started in July 1985.71 Mr Munday had trained as an engineer and then lectured in the subject, but had had a parallel ‘career’ as church organist wherever he lived for the previous forty years.72

By 1987, Mr Munday had become increasingly concerned about the general state of the organ. The effects of wear and tear could no longer be remedied by routine maintenance and he believed a major overhaul was needed.73 Since this was likely to be prohibitively expensive, he presented a report to the PCC in November 1987 recommending its replacement with a modern pipeless organ. The PCC agreed with the proposal, but no immediate action was taken.

By 1987, Mr Munday had become increasingly concerned about the general state of the organ. The effects of wear and tear could no longer be remedied by routine maintenance and he believed a major overhaul was needed.73 Since this was likely to be prohibitively expensive, he presented a report to the PCC in November 1987 recommending its replacement with a modern pipeless organ. The PCC agreed with the proposal, but no immediate action was taken.

In 1989, a faculty was granted to provide choir stall book rests with wrought iron supports.

In June 1990, the organ was inspected by Henry Willis & Sons and the bellows were found to be in need of urgent repair. Further bad news came in the following year when woodworm infestation was discovered in part of the sound board. An organ subcommittee was established, meeting for the first time on 16th September 1991, to explore the options and recommend a course of action. Mr Munday was initially a member of the subcommittee, but retired as organist and choirmaster at the end of 1991. As an interim measure, the rector, Philip Humphreys looked after the choir.74

The subcommittee commissioned inspections of the organ in March 1992. The reports found: “This was obviously a very fine organ at one time, although the present tonal quality leaves a great deal to be desired. Many notes are not speaking.” “After 40 years, the electrical part of the system is now giving considerable trouble.” “The manual windchests have faults on them that cause unwanted notes to sound at any time.” “Re-instate the double rise bellows to its original form. The present system was installed as a temporary measure, and does not give the stable wind supply required.” “Certain ranks do not sound as regular as they should, nor of the correct strength.” “I find it most regrettable to see an organ without a proper case in such a fine building.” “The musical problem of the player being some 20 metres away from the main organ, with the choir in between. This must make it extremely difficult to achieve good results even when playing the standard repertoire.”

These reports confirmed the view that a new, electronic organ would be the best way forward and demonstrations were arranged to be held in St Giles’ during September of two organs, a Makin MD355 and an Allen MDS-40S. These included a recital by the rector, Philip Humphreys, who was an accomplished pianist, to show how effective the instruments could be even without a trained organist. The demonstrations received a very positive response from the congregation and the Allen organ was judged to have the better sound qualities.

An appeal75 was launched to raise the £25,000 required and, this being successful, the new Allen organ76 was duly installed in October and November 1993. The console was in the usual place, behind the southernmost choir stalls, with the loudspeakers at the south side of the north chapel.

An appeal75 was launched to raise the £25,000 required and, this being successful, the new Allen organ76 was duly installed in October and November 1993. The console was in the usual place, behind the southernmost choir stalls, with the loudspeakers at the south side of the north chapel.

Sets of pipes were retained for decoration.

Sets of pipes were retained for decoration.

These include pipes from the original Lloyd organ and the choir organ added by Willis, as well as some of the non-sounding pipes.

It was a further eighteen months until an organist was appointed.

During that period, the work of directing the choir and providing music was shared between Philip Humphreys, Daniel Humphreys, Fred Munday and Arthur Smedley.

Then, in February 1995, Mr Alan J Hindle was appointed organist and choirmaster.77 He had had a career in education, including Head of Music at Frank Weldon Comprehensive School and as an OFSTED inspector of Secondary School Music Departments.

Then, in February 1995, Mr Alan J Hindle was appointed organist and choirmaster.77 He had had a career in education, including Head of Music at Frank Weldon Comprehensive School and as an OFSTED inspector of Secondary School Music Departments.

Mr Andrew John Rootham followed Mr Hindle as Director of Music in September 2002.

Mr Andrew John Rootham followed Mr Hindle as Director of Music in September 2002.

Under his leadership, music at St Giles’ diversified to include worship bands and a junior choir, allowing the church to offer both traditional style worship and a more contemporary style. Mr Rootham died in May 2015 after a short illness; he was 48 years old.

Dr Paul Bracken was appointed organist from the beginning of November 2015. Dr Bracken teaches piano and singing, as well as performing widely as a pianist.78

Dr Paul Bracken was appointed organist from the beginning of November 2015. Dr Bracken teaches piano and singing, as well as performing widely as a pianist.78

He has Lay Ministry qualifications in Christian Education and Music and Worship; his Ph D in musicology was based on research into medieval French songs.

The well-established robed choir has a large library of choral music – now including many items composed or arranged for them – and sings a wide variety of traditional Anglican Church music (SATB choral pieces by Byrd, Tallis, Bach, Purcell etc.) as well as some Taizé and Gregorian Chant. The choir sings at about 75 services each year, including: Choral Eucharist every Sunday at 9 am, Choral Evensong on the First and Third Sundays of each month at 6 pm, and various special services for Christmas and Easter.

In preserving the venerable tradition of Choral Evensong, St. Giles’ Choir are acknowledging an important aspect of local heritage. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), who devised not only the service of Evensong but also the entire Book of Common Prayer (1549 – revised 1552 and 1662), was born just a few miles away in the Nottinghamshire village of Aslockton. As a leading Evangelical and reformer of the English Church, who was also connected with Lady Jane Grey’s political faction, Cranmer’s martyrdom under the Catholic Queen Mary was almost inevitable. He was burned in front of Balliol College in Oxford on 21st March 1556 after an elaborate show trial. Consequently, he has no known grave. However, the incised marble tomb-slab of Thomas’s father, also called Thomas, who died in May 1501 can be seen in the church of Whatton, a tiny village very close to Aslockton. Nevertheless, Thomas Cranmer, the ‘quiet man of God’ is remembered at St Giles’ every time the choir sings the lovely service of Evensong at 6 pm on the first and third Sunday of each month (except during August) using the 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer.

Reinforcing the diversification in worship style, Mrs Hannah Crawford was appointed, at the same time as Dr Bracken, as Worship Director for the Informal Worship services at 10.30 am on Sundays.

ORGANISTS

The following list of appointed organists is believed to be complete from 1895 onwards.

| 1871 | - | 1875 | William Gunn |

| ? | |||

| 1884 | - | 1892 | William Stevenson |

| ? | |||

| ? | - | 1896 | Florence Ackroyd Kirk (née Pemberton) |

| 1897 | - | 1898 | Cicely Tomkins (née Crisp) |

| 1898 | - | 1904 | James Buckland Lyddon |

| 1904 | - | 1905 | Vernon Read |

| 1905 | - | 1907 | James Buckland Lyddon |

| 1908 | - | c1912 | William Ryde |

| c1912 | - | 1920 | Cicely Tomkins (née Crisp) |

| 1920 | - | 1924 | Charles Bissill Morris |

| 1924 | - | 1941 | George Dudley Newball |

| 1941 | - | 1957 | John Gordon Wood |

| 1957 | - | 1961 | Malcolm Courtenay Boyle |

| 1962 | - | 1965 | Harold E F Bebbington |

| 1965 | - | 1970 | Walter L Rogers |

| 1970 | - | 1984 | A Walter Esswood |

| 1985 | - | 1991 | Fred G Munday |

| 1995 | - | 2002 | Alan J Hindle |

| 2002 | 2015 | Andrew John Rootham | |

| 2015 | - | Paul Bracken |

REFERENCES

1 C H B Watson West Bridgford Church Transactions of the Thoroton Society 1941

2 R F Wilkinson The Music and Organs 1951

3 Nottinghamshire Guardian 11th September 1868

4 Nottinghamshire Guardian 3rd October 1873

5 Nottinghamshire Guardian 1st January 1875

6 Nottinghamshire Guardian 31st December 1869

7 Nottingham Evening Post 1st January 1934

8 Nottinghamshire Guardian 26th September 1884

9 Nottingham Evening Post 26th April 1892

10 West Bridgford Bazaar Illustrated Hand-Book 1895

11 Bazaar Souvenir Programme 1938

12 Church Extension Council Minutes 12th May 1895

13 Church Extension Council Minutes 3rd June 1896

14 Church Extension Council Minutes 24th December 1895, 3rd June & 15th July 1896

15 Nottingham Evening Post 17th November 1941

16 Church Extension Council Minutes 10th December 1896, 28th January 1897

17 Church Extension Council Minutes 25th November & 10th December 1896, 31st March 1897

18 Church Extension Council Minutes 27th April & 24th May 1898

19 Church Extension Council Minutes 27th September 1899

20 Church Extension Council Minutes 26th October 1898

21 Church Extension Council Minutes 1st December 1898

22 The London Gazette 16th December 1898

23 Church Extension Council Minutes 1st December 1898

24 The Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury 15th December 1899

25 Nottinghamshire Guardian 25th November 1899

26 Church Extension Council Minutes 27th September 1900

27 Church Council Minutes 31st January, 29th October & 3rd November 1902

28 Church Council Minutes 7th June 1903

29 Church Council Minutes 21st March 1903

30 Church Council Minutes 4th July 1904

31 Church Council Minutes 5th September 1904

32 Nottingham Evening Post 27th March 1893

33 Nottingham Evening Post 9th September 1939

34 The Western Times 17th October 1947

35 St Giles Parish Magazine February 1905

36 Nottingham Evening Post 19th December 1907

37 St Giles Parish Magazine February 1908

38 Nottingham Evening Post 22nd July 1947

39 Nottingham Evening Post 4th October 1923

40 Nottingham Evening Post 25th November 1950

41 Nottingham Evening Post 20th May 1912

42 R F Wilkinson The Music and Organs 1951

43 Nottingham Evening Post 17th July 1920

44 Dictionary of Organs and Organists Geo Aug Mate & Son 1921

45 Nottingham Evening Post 13th May 1930

46 Nottingham Evening Post 6th February 1925

47 Nottingham Evening Post 12th April 1930

48 Nottingham Evening Post 26th September 1941

49 Nottingham Evening Post 15th December 1936

50 Nottingham Evening Post 19th December 1933

51 Nottingham Evening Post 9th October 1936

52 Nottingham Evening Post 8th April 1949

53 R F Wilkinson The Music and Organs 1951

54 R F Wilkinson The Music and Organs 1951

55 Dedication of the Organ 1952

56 St Giles PCC – Organ Subcommittee minutes

57 The Times 14th October 1963

58 St Giles Parish Magazine December 1956

59 St Giles Parish Magazine July 1957

60 Robert Evans, Maggie Humphreys Dictionary of Composers for the Church in Great Britain and Ireland Bloomsbury Publishing 1997

61 St Giles Parish Magazine June 1958

62 St Giles Choir Committee Minutes 13th April 1956

63 St Giles Choir Committee Minutes 12th April 1957

64 St Giles Parish Magazine December 1961

65 St Giles Choir Committee Minutes 25th June 1964

66 St Giles Parish Magazine December 1965

67 St Giles Parish Magazine February 1968

68 St Giles Parish Magazine November 1967

69 St Giles Parish Magazine December 1970

70 St Giles Parish Magazine November 1984

71 St Giles Parish Magazine July 1988

72 St Giles Parish Magazine December 1991 / January 1992

73 St Giles PCC – Organ Subcommittee minutes

74 St Giles Parish Magazine March 1992

75 Organ Appeal leaflet 1992-1993

76 MDS 40-S Owners Manual

77 St Giles Parish Magazine March 1995

78 St Giles Parish Magazine December 2015

79 Sheila Leeds – a member of the orchestra for most of those years