The first known record of West Bridgford is in the Domesday Book of 1086, but it makes no mention of either a church or a priest.iv West Bridgford was then part of the Manor of Clifton. At the time of the conquest, the Lord of the Manor was Countess Gytha (of Hereford), but by the time of the Domesday Book, the Lord of the Manor was William Peverel. In 1171-2 the King granted West Bridgford and its soc to Gerbode de Eschaud; then, at some time during the reign of Richard I (1189-1199), lands in Clifton passed from Gerbode to Gerard de Rodes. In 1201, the King confirmed Gerard’s gift to Geoffrey Lutterel of his demesne and 16 bovates in West Bridgford. When his descendant, Andrew Lutterell died in 1265, he was said to hold “the advowson of the church of Bridgeford of Gerard de Rodes”.v

Thus we can conclude that a church was built in West Bridgford before Lutterell became Lord of the Manor, and certainly before 1201. Whether this church was St Giles’ or whether there was an earlier church – one suggestion, although from a barely credible source, was that the original site of the church was somewhere called Barrack Close, near the village pinfoldvi – it is impossible to say.

Lutterell either improved on the original construction or built his own to replace it. A study of the stonework, particularly around the priest’s door in the ancient chancel, coupled with the architectural styles reveals that the church was built in stages.

The priest’s door and the double square piscina and aumbry are in the Early English style, which generally accords to the period 1180 to 1275.

Although there is no documentary evidence that St Giles was the original dedication of the church, many churches were dedicated to St Giles around this period. Various estimates have been made as to exactly when St Giles’ was first built: Barratt placed it at around 1230vii while Gill put it as early as 1191viii.

The first surviving mention of a priest is the institutionix of Luke de Crophill on 14 October 1239, with the patron being Sir Andrew Lutterell, the son of Geoffrey. When Andrew died, a valuation of the advowson of West Bridgford was made in 1265 at 20 marks i.e. £13 13s 4d.x As well as West Bridgford, the parish included the hamlet of Gamston and part of Basingfield. At both Basingfield and Gamston there were places called Chapel Yard, which would suggest they had chapels in ancient times.xi

In the Taxation Rollxii of Pope Nicholas IV, compiled between 1291 and 1292, the benefice was valued at £17 6s 8d.

At the time of the visitation of Archbishop Corbridge in 1302, Robert Lutterell was the incumbent. He failed to appear and was pronounced contumacious, but contrived to make his peace with the prelate, who shortly afterwards gave his permission for absence and ordered his officials not to molest him.xiii

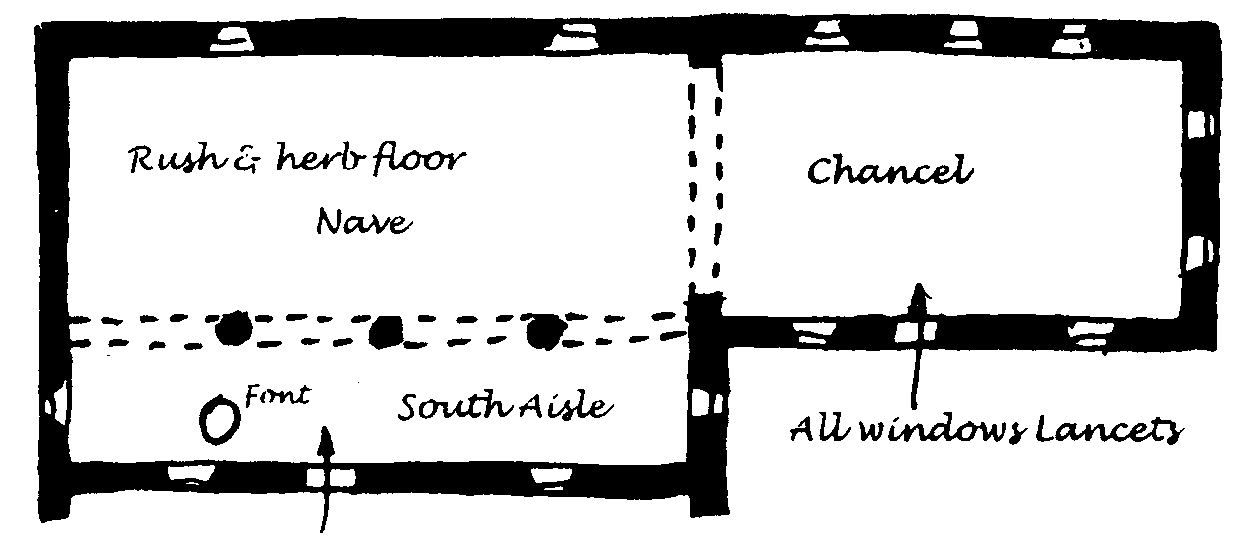

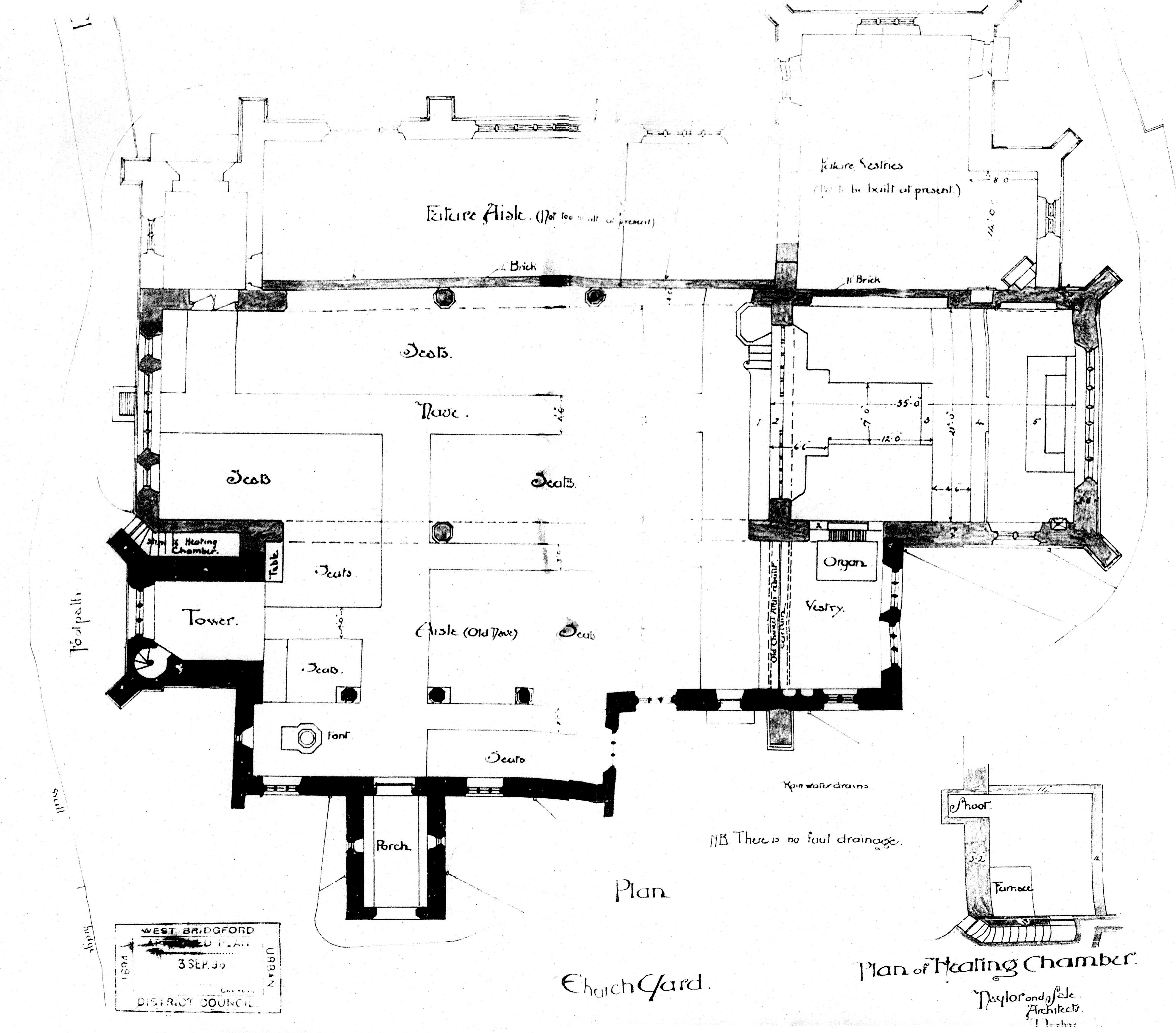

The original church of St Giles’ was built on a simple planxiv, commonly used in village churches. Although church buildings are traditionally aligned so that the altar is at the east, the alignment of St Giles’ is a little astray, with the altar at east-north-east.

The lower part of the walling, which can be attributed to the original building, is built of “skerry” or “water-stone” obtained locally. The walls would have been much lower than today, with a high pitched roof, as is evidenced by the corbels still to be found part way up the walls of the south aisle.

Samuel Dutton Walker, in 1863xv, also remarked on how the steep roof was also evidenced by the fact that the chancel arch could be seen to be above the then roof of the chapel. The building would have been quite dark inside, with lancets for windows, similar in size and shape to the one now at the west end of the south aisle. Gill was of the view that this particular window was a later renewal of an earlier window but it is known that, until the enlargement of the church in 1898, there were two such lancets in the north wall of the chancel.xvi

In 1341, a subsidy of “ninths” of the yield of corn, lambs and wool was granted to the king by the lords and commons of England to pay for Edward the Third’s wars in France, and the various assessments are given in the “Nonae” or “Ninths” roll. The value of the benefice of West Bridgford at this time was assessed, for taxation purposes, at 26 marks, again £17 6s 8d.xvii

During the fifty years’ reign of Edward III (1327-1377), village churches were enlarged or rebuilt in order to meet the needs of the more elaborate ritual then in vogue. It is interesting to note that John de Aslacton, junior became rector in 1349 and, when the walls of the church were stripped of plaster in 1871, the arms of the Aslacton family were found to be painted on the western sidexviii. This may have been in recognition of money being spent by the Aslacton family, of Nottinghamshire, in rebuilding the north wall of the chancel. The rector was solely responsible for the fabric of the chancel while the Lord of the Manor and the villagers contributed to the upkeep of the nave, so there was more money available for the new style of the Decorated period to be introduced in the nave than in the chancel.

Flowing tracery of the Decorated period can be seen in the east window of the old south aisle and in two windows, taken from the the old north wall of the church in 1898 and eventually placed in the choir vestry.xix

The triangular window that was in the east wall of the chancel – but is now preserved in the porch – is typically ‘curvilinear’.

The southernmost of the twin windows at the east end of the old chancel is also from this period. It has been noted that the tracery of these windows was each cut from a single piece of stone.

The fourteenth century was a time when many chantries were founded in England. Although there is no documentary evidence that St Giles’ had a chantry, there are indications that the south aisle was once used for this purpose. A double piscina,with stone carving of the Decorated period, is set in the wall and indicates that there was once an altar here.

The area was certainly set aside as a chapel. During the restoration of 1871, the foundations were discovered which would have carried a screen to enclose the chapel.xx Indeed, a pillar still displays a groove into which a screen may have fitted.

Finally, there is the sedilia built into the south wall at the east end, with two seats of equal height. Large churches may have had three seats but a village church would normally have a single seat. An explanation for the second seat could be that the second seat was for the chantry priest who assisted the rector at the mass.

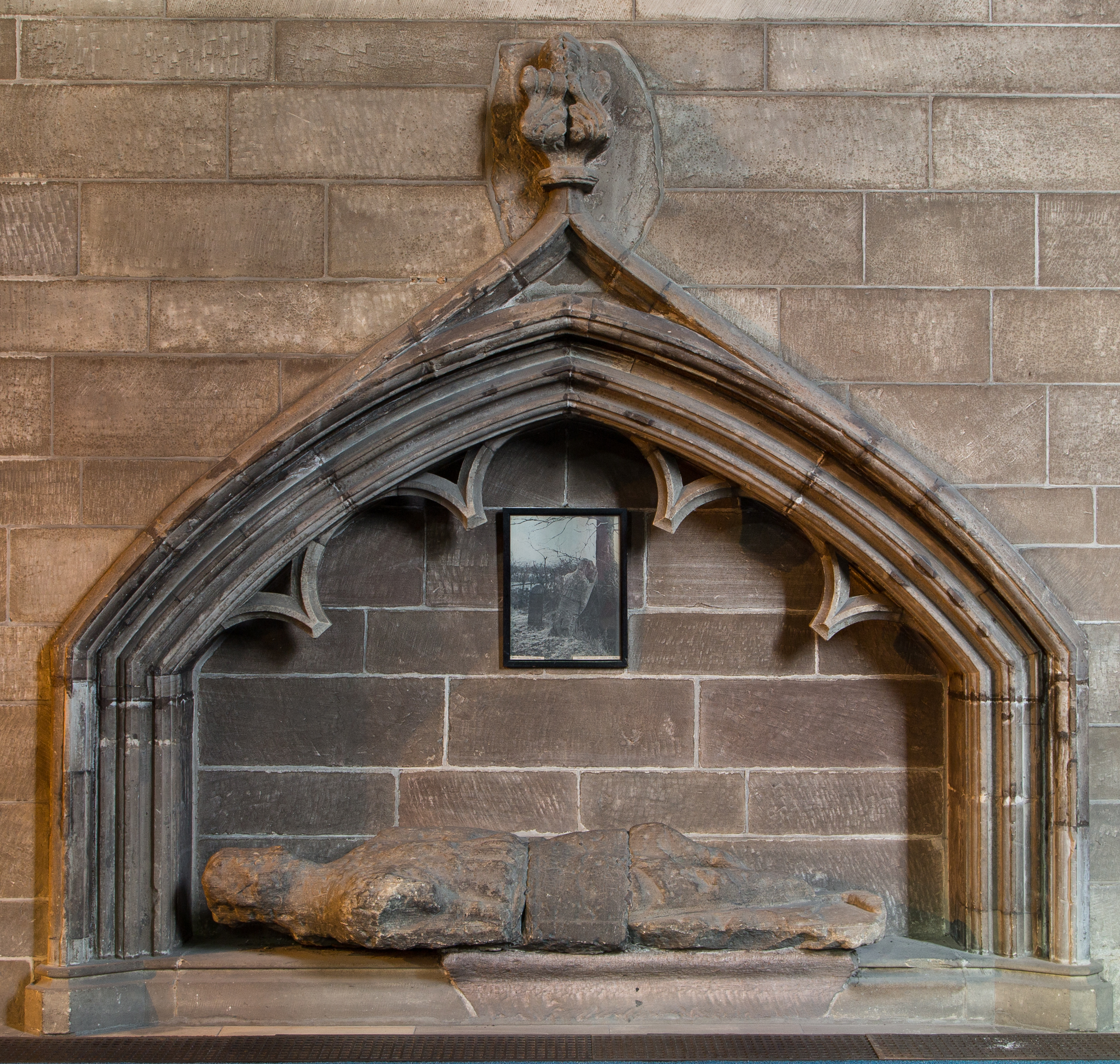

There used to be a low canopied arch of fourteenth century design in the north wall of the old chancel. This was moved when the church was extended, and is now to be found, much restored, in the north wall of the new north chapel. It houses West Bridgford’s ‘Stone Man’. The effigy was retrieved from a nearby field in the 1890s and placed in its new home. There has been much speculation – and indeed a poem extending to 29 pages – as to the origin of the Stone Man, but the evidence is lacking to enable a firm conclusion to be drawn.

All writers are agreed that the south porch has undergone much alteration over its lifetime. Watsonxxi was of the view that it was added in the fourteenth century, but others have judged it to be earlier. Walkerxxii described it as ‘probably of Early Decorated date’ and Godfreyxxiii as ‘of the Early English period’ in keeping with the chancel, nave and aisle. A narrow window in the porch is cut from a single piece of stone and has markings around it.

It has been conjectured that the vaulted roof of the tower once formed the roof of the porch. In the nineteenth century, the porch had a heavy medieval oak door – presumed to have been removed from the inner doorway – with a key fifteen inches long.xxiv

To the west of the porch is a blocked-up doorway. There have been various suggestions as to its origin: the original doorway to the church;xxv entrance to a stairs leading to a room over the porch;xxvi or the entrance to an area set aside as a schoolroom.xxvii At one time, there was a doorway on the north side of the nave: this was revealed during the restoration of 1871, when it was described as having been “disused some centuries”.xxviii

The octagonal font is fourteenth century and would presumably have originally stood just inside the south door.xxix

Another fourteenth century addition was the rood screen, which was dated by Vallance as about 1380.xxx

In the 1428 subsidy tax records of Henry VI, the value of the church is again 26 marks, while the subsidy (i.e. tax) was one-tenth of this, at 34s 8d.xxxi

About the same time as the rood screen was installed, there was a widespread desire in England for still more light and loftiness in parish churches. In West Bridgford church, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the old arcade was removed, and a new one of early Perpendicular style built. On the south side it supported the raised wall of the nave, which was pierced by four two-light clerestory windows. On the north side the existing walls were made higher to take a similar group of clerestory windows. The three pillars and moulded capitals of the present arcade are octagonal, and the responds of the eastern and western arches are carved with grotesque faces, similar to those supporting the chancel arch, which was built at the same period. A new roof was constructed in the Perpendicular style, with its trusses resting on grotesque corbels. Externally a parapet with battlements was superimposed on the raised walls.xxxii

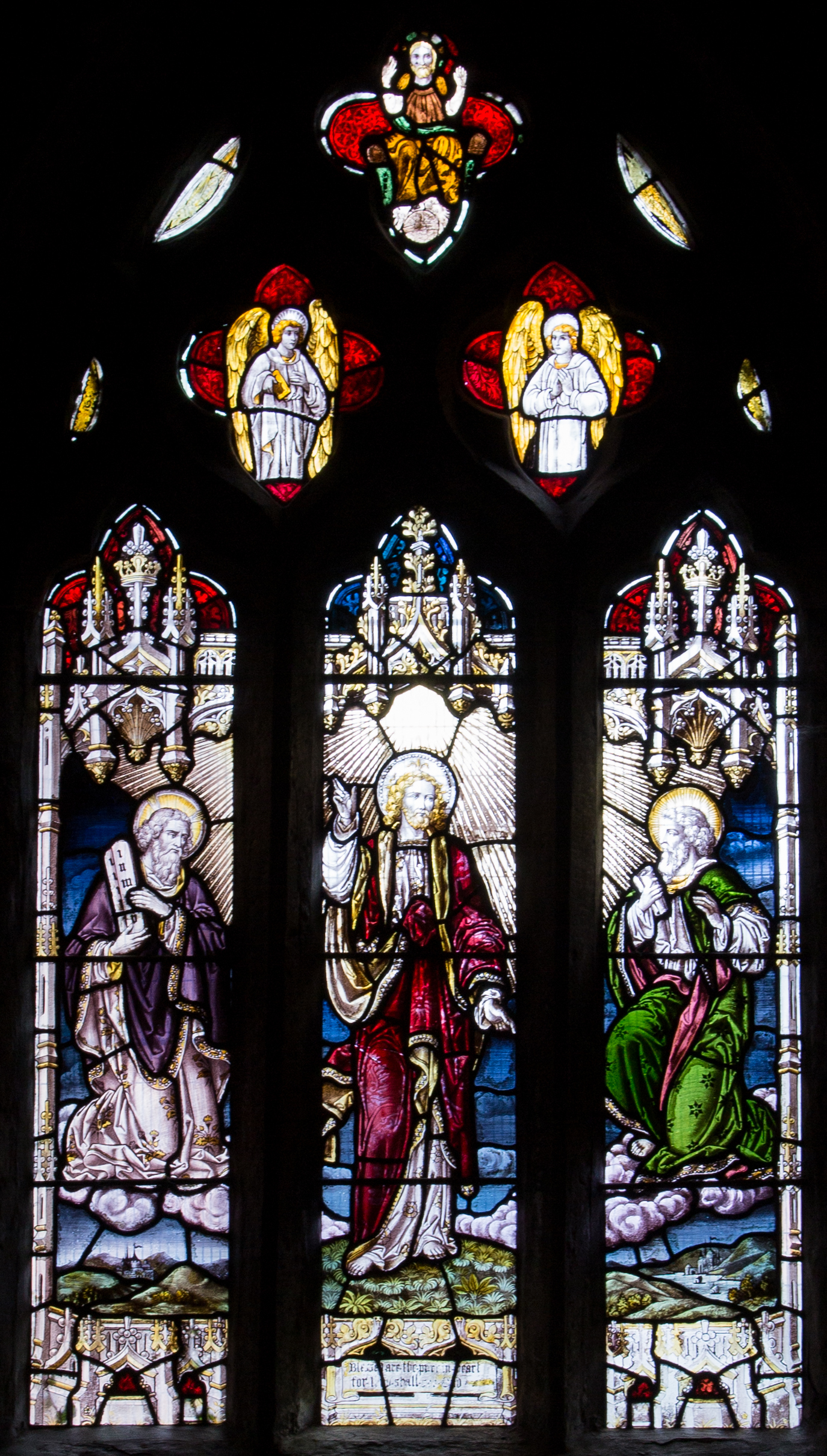

Medieval churches were very colourfully decorated and St Giles’ was no exception. The medieval stained glass has been described by Walkerxxxiii, while Phillimore described the decoration uncovered during the 1871 restoration.xxxiv The whole of the chancel had once been decorated. The stonework of one window was painted to represent sienna and white marble; another was painted in green and vermilion; and elsewhere a dull red was used. The rood screen was green.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, some alterations were made in the chancel. The two older windows in the south wall were replaced with new ones in a debased Gothic style.xxxv

Walkerxxxvi wrote that the tower was built around 1600, but this may have been a printing error as others have placed it to be early in the sixteenth century. The tower has no west door into the church but, in 1863, Walker remarked that “a modern debased one has been inserted on the south side, probably for the convenience of the bell-ringers”. This doorway was blocked up in the restoration of 1871.

There is an inscription on the south side of the tower. The stone is unusually high on the tower and it has been remarked that “there seems to be no connection with tower, and when and why it was placed there is unknown”.xxxvii Although it is accepted that the text translates as “Christ the stone of help”, there was considerable debate on the exact deciphering of the letters. Watson favoured the rendering of the old English lettering as “xhr lapis adjutori”.xxxviii

Walker and others have also said they can see an inscription under the south-eastern pinnacle of the tower, but no-one has claimed to decipher it.

In the Valor Eccelsiasticus of 1536, the annual value of the rectory was given as £16 14s 2d, while a pension of 2s had to be paid to the rector of Holme Pierrepont.xxxix

The Commissioners of Church Goods, on 6th May1553, handed over to Walter Basse, parson of West brydgeford, “one chalice of sylver & p’cell yr off gyldede wt a patente for ye admynystrcon of ye holy comunyene as also thre bells of one accorde hangynge in ye style of ye same churche”.xl Neither of the communion vessels have survived.

Church registers started to be kept in 1559, with the initial volumes in vellum.

From the visitation of 1567, we learn that Nich. Coke, the rector of Rosse, was “also parson of Bridgeford in Nottinghamshire, and being not resident at Rosse distributeth not he xlth parte”.xli (The list of rectorsxlii from the Torres MSS, give the rector at this time as “Joh Cooke”. Rosse is most likely to be Roos in east Yorkshire.)

A series of Churchwarden Presentments starts in 1587.xliii An entry for that year records that “our curate doth refuse to wear the surplice and did not wear it Easter last”. The curate was Nicholas Hallam, who repeated the offence at Trowell in 1591 resulting in a temporary excommunication.xliv

The parish registers note that, in 1593, “the Plague was in Nottingham and in some places in West Bridgford”.

In 1603, it was reported that there were no recusants in the parish, about two hundred and twenty communicants and no non-communicants.xlv

The Protestation Returns of 1641/42 listed those males over the age of 18 who took, or did not take, an oath of allegiance “to live and die for the true Protestant religion, the liberties and rights of subjects and the privilege of Parliaments”. In the parish of West Bridgford with Basingfield and Gamston, the list was of those males aged over 16 and none refused. The names of those who took the oath included Francis Withington, rector and Joshua Siston, curate.xlvi

The rectors of West Bridgford suffered repercussions from both sides of the Civil War. In 1643, Francis Withington was taken into the custody of the House of Commons and his living was sequestered.xlvii It was given to Samuel Coates on 15th May 1648. xlviiiDuring the war, Royalist forces made a number of attacks on the Parliamentarian-held Nottingham. In April 1645, the fighting spilled over into West Bridgford: “The Newark horse, since they took the Trent Bridge fort, … have done much mischief to adjacent towns thereabouts, … and particularly at Bridgeford, where they did not only plunder the inhabitants, but carried away every man prisoner that they found in the town. Six of them fled into the church, thinking thereby to save themselves, but they brake open the Church doors, and brought them away prisoners”.xlix

The Parliamentary Commissioners of 1650 valued the rectory at four score and ten pounds per annum, which the incumbent Samuel Coates, a “godly able preaching minister” received to his own use.l After the civil war, following the Act of Uniformity in 1662, puritan ministers were forced out of their positions. Amongst the ejected clergy was the rector of West Bridgford, Samuel Coates. He has been described as a profound scholar who preached substantial divinity, albeit with “an unacceptable kind of stammering in his delivery”. In later life, it was said that “his name was precious in all the neighbourhood for his labours, piety and charity”.li

The parish registers note that there was a summer flood at Swithin (July) 1692.

Joseph Bruen became rector in January 1692/93 and discovered that the new Lady of the Manor of West Bridgford, Mrs Fuller, had enclosed areas of common grazing ground during the period between the death of the previous rector, Thomas Haughton, in September 1692, and his own institution. When Mrs Fuller carried out further enclosures in 1710, Bruen brought a court action against her to claim the rights of grazing that had been held by the rectors of West Bridgford.lii

In 1699, it was reported that the chancel was out of repairliii and when John Stokes senior became rector in 1717, he found that not only the chancel of the church but also the parsonage was in poor repair. A detailed estimate for carrying out all the work – including glazing the chancel windows – has survived.liv The work on the parsonage and outbuildings was quite substantial, with the estimate providing for 1,000 tiles and 3,400 nails.

In 1835, Barker reported finding that “within the rails, near to the communion table, are the following initials and dates, all referring to different persons of the family of Stokes: E.S. 1758 – R.S. 1779 – A.S. 1786 – R.S. 1802 – M.S. 1806”.lv Godfrey reported that memorials to Millicent Stokes (daughter of John Stokes, junior) and her son, Robert James Fisher, were also once in the chancel. These memorials were removed to the north wall of the old nave, presumably in the 1871 restoration, and then moved, as part of the church extension, to where the ringing chamber now is in the tower.lvi

The parish registers note that: “In Bridgford Parish Gallows set nere to Wilford Lane in Bridgford Lordship August the ninth and a man hanged August the tenth and buried under the gallows 1726. No one ever knew gallows to stand in the Lordship before.”

In 1743, Archbishop Herring asked a number of questions of parishes. The replies of the rector of the time, John Stokes junior, paint a picture of the parish of West Bridgford. There were just 51 families in the parish, two of whom were Dissenters i.e. not members of the Church of England. He estimated that there were about 150 communicants in the parish, but only about twenty who usually received communion. Stokes lived in the Parsonage house and had no curate.

The churchwardens’ accounts survive for the period 1759 to 1836 and also tell their story of parish life.lvii For example, the entries for 3rd September 1759:

for 36 children’s dinners at the confirmation 12s 0d

for ale for them 4s 4d

Also, there are entries for repairs including, on 18th June 1761, what was to be a recurring problem:

pd to John Birch for the new pinnacle and other repairs £5 5s 0d

The terrier for 1777 described the rectory house as consisting of two parlours, a kitchen, brewhouse, dairy, cellar, six rooms above stairs, and an outhouse containing a stable with three stalls, a coalhouse and a coach house. There was also a “hovel”, eight yards long, and a dovecote, four yards square.lviii

The accounts also show that a vestry was built in 1786:

24th December 1786 pd for building the Vestery £10 10s 0d

The parish registers contain a memorandum concerning the first school in the village in 1786 and the accounts have an entry for 30th March 1792:

to childrens school wage 10s 6d

The school had been established by the rector, William Thompson, with the permission and assistance of John Musters in 1778. When Thompson died, his willlix provided £18 per annum “to a proper person … to instruct the children of such labourers and manufacturers in the parishes of West Bridgford and Colwick as should be deemed too poor to pay for them, in the rudiments of the Christian religion, reading, writing and accounts” and £9 per annum “toward clothing … or purchase of books or repairs of the school and dwelling-house, then inhabited by Samuel Whites”. The first payment from this endowment appears to have been made in 1822. The children to benefit from the endowment were to be chosen by the rector of the time, however there were few poor people in the two parishes and it was not easy to find the ten children who received the support.

In October 1794 a flood damaged surplices and cushions in the church and fires were lit for six days to help dry it out.

When Throsby visited the parish at the end of the 18th century, he was told that there were no Dissenters in the parish, and he found the church “well pewed and kept clean”.lx

Until well into the nineteenth century, it was common for the rector of West Bridgford to have responsibility for another parish. Indeed, the living was held alongside that of Colwick from 1749 to 1862.lxi This could have its benefits. In 1771, the rector, William Thompson was also vicar of Colwicklxii which may explain how he came to marry Miss Gaylin of that village, “a lady endowed with every genteel accomplishment and a plentiful fortune”.lxiii Thompson kept a rain gauge from 1st August 1793 and published details of the rainfall at West Bridgford.lxiv

In 1807, a singing loft was installed in the tower at a cost of £22 19s 6d.lxv

A terrier of 1809 describes the parsonage in some detail and the other buildings: the main out building containing stables, coach house and coal house; two barns; two pig sties; and a dovecote. The terrier also sets out the land owned by the church and the tithes due to the rector, as well as the silver owned by the church. At this time, the parish was still responsible for the repair of the body of the church, while the rector was responsible for the chancel, parsonage house and all the other out buildings.lxvi

The rectors of Gamston had had many disputes over the division of tithes and, in 1809, an Act of Parliament was obtained for apportioning the shares.lxvii

In 1811, £3 11s 0d was paid for whitewashing.lxviii This must have been the first time the walls of the church were whitewashed as, ironically, Laird had just previously visited St Giles’ and remarked that “its interior is kept in very neat order, which the annual beautifiers have not yet begun to whitewash”.lxix

In 1813, one of the church bells was replaced.lxx

Stretton visited St Giles’ in 1816 and his description of the church can be found in Godfrey’s Notes on the Churches of Nottinghamshire.lxxi He remarks that the church has had a shingled roof, but now leaded. The timbers of the ancient oak roof were exposed and supported by corbels. “The pewing is modern, of deal, neat and uniform, King’s arms modern, the Creed and Lord’s Prayer over it. The cancelli of oak, plain Gothic work, but no rood loft.” The remains of the deal pews can be seen still on the walls of the south wall after the restoration of 1871.

Today, they survive as the ceiling of the porch.

It has been suggestedlxxii that the mutilation of the pillars was done to accommodate the pews.

Stretton added: “The east end of this chancel has been very justly remarked and admired for the beautiful and peculiar construction of its windows, which Mr Blore observes are not equalled in any village church that he has seen. There are three of these windows, two below, and one above them, filling up the gable end, … and enriched with beautiful tracery, but the tasteless depravity of the churchwardens bricked them up to save the expense of glazing and repairs.” The photograph shows the bricked up windows.

A terrier for 1817 gave much the same information as that for 1777.lxxiii

White’s directory for 1832 described St Giles’ as “a fine edifice, which appears to great advantage peeping over the trees that surround it. The benefice is a rectory, valued in the King’s books at £16 14s 2d.”

Sir Stephen Glynne visited on 19 April 1833 and made notes on the church.lxxiv

The chancel was repaired “at considerable expense” in 1833.lxxv The work appears to have included re-roofing the chancel. A flat ceiling was put in, blocking up part of the two main east windows, the easternmost lancet window on the north side of the chancel was walled up, and the exterior stuccoed to represent masonry. Benches – said to have come from St Mary’s, Nottingham – had been in the chancel, but these were replaced by square pews. The singing loft over the chancel screen was removed, together with the staircase on the south side that led to it.lxxvi

In a return of 1835, it was stated that West Bridgford had a glebe house unfit for residence.lxxvii

The tithes were commuted in 1840 for £262.lxxviii The total assessment had been £1,990, with John Musters owning 19/20 of the land. The agreement was signed by every landowner and tithe owner in the parish.lxxix

In 1851 the religious censuslxxx gave details of West Bridgford parish, which still included Gamston and part of Basingfield. The population of West Bridgford township was 258, with a further 124 in Gamston and Basingfield. St Giles was endowed with a rent charge of £550 and glebe £90. There was seating for 183, with 33 of those being free. The average congregation was given as:

|

Morning |

Afternoon |

Evening |

|

|

General Congregation |

65 |

100 |

40 |

|

Sunday Scholars |

33 |

33 |

– |

In November 1852 the Trent flooded the whole of the village of West Bridgford. “The churchyard, all the streets and gardens were flooded, and on Sunday it was impossible to perform Divine Service, the church being almost entirely isolated from the rest of the village.”lxxxi

William Roe Waters became rector in 1862, when West Bridgford was still just a hamlet, but he was to live to see its rapid expansion into a town. His obituary described him as belonging “to an old-fashioned school of country clergymen, which is rapidly becoming extinct, but he adapted himself to the requirements of a suburban population, and, besides being a zealous worker, a capital organiser, and an effective preacher, was much esteemed for his geniality and the deep interest he took in the welfare of his parishioners”.

When Waters arrived, the rectory was “scarcely fit to reside in”.lxxxii Indeed, the previous rector, William Musters, had been granted permission not to reside in the rectory on the grounds of his ill-health and the lack of repairs to the rectory.lxxxiii Waters obtained a grant of £200 from Queen Anne’s Bounty and a mortgage of £1,070 to build a new one in 1863, using the plans of the Nottingham architect, Robert Evans.lxxxiv (In the same year, Walker averred that it had “been built in good taste and style”.lxxxv He was less flattering about the vestry which he said “might by many persons be easily mistaken for one of those useful and convenient little buildings generally seen at the extreme end of the gardens attached to the cottages of labouring men, so plain and bald is its form”. He went on to describe the church in some detail.) A small school was established in 1865, on land given by John Chaworth Musters on Rectory Road, and twice enlarged during his time. The church itself was dilapidated, still with the old-fashioned high-backed pews, and many of the most striking architectural features covered up.lxxxvi

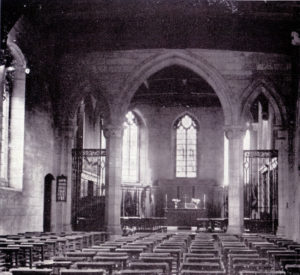

The picture shows the church at this time, before the restoration of 1871. Walker wrote that the “vile-looking brick chimney-stack rears its head and destroys the harmony and ecclesiastical appearance of that part of the building”.lxxxvii

Aided by a grant from the Incorporated Society for Promoting the Enlargement, Building , and Repairing of Churches and Chapelslxxxviii, Waters embarked on a major restoration of the church on 11th August 1871. According to Pevsner, the architect for the alterations was Thomas Chambers Hine,lxxxix although a contemporary source has not been found to confirm this.

The restoration saw the obliteration and removal of the decoration from medieval times. The thick medieval door was burnt, the glass removed, and the walls scraped bare. The pews, “many of them handsomely carved in various designs”, were replaced with varnished pine benches. The lath and plaster partition between the top of the chancel screen and the arch, on which were the royal arms, was removed. The chancel walls and roof were raised a couple of feet. The triangular window was raised two feet six inches, and the old red stone tracery replaced by new work in white stone. The middle north lancet window in the chancel was converted into a doorway for a new vestry, and the westernmost window became the arch for an organ chamber. Two alabaster sepulchral slabs in the chancel were cut up to form the communion step.xc An organ was bought from Sneinton Church and installed in the organ chamber.xci

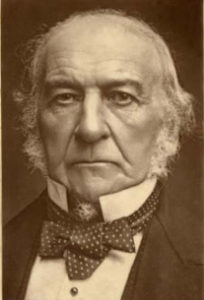

A new gargoyle was inserted at the south-east angle of the nave. Barratt remarked that this “bears an uncanny likeness to W E Gladstone”.xcii

A new gargoyle was inserted at the south-east angle of the nave. Barratt remarked that this “bears an uncanny likeness to W E Gladstone”.xcii

The restoration cost £800. Other work included: building a new vestry; the bellringers’ doorway in the tower was blocked up; the musicians’ gallery under the tower was taken down; the font was moved into the tower; and the rood screen was removed, cleaned, and replaced.xciii

Phillimore decried the loss of so much that he thought should have been preserved, but others spoke more warmly of the restoration. The Nottinghamshire Guardian reported the 1873 harvest festival as taking place in “the beautiful restored church of West Bridgford”. At the evening service “the church was crowded to excess, chairs having to be placed in the aisle for the accommodation of those who could not be seated in the pews”. The report concluded by saying that “the rector is also to be congratulated on having restored the church in so beautiful a style, bearing as it does such a happy contrast with its appearance previous to restoration”.xciv The report of Christmas 1874 called St Giles’ a “pretty little village church” and remarked of the decorations that “the whole (seen by gaslight especially) presents a charming appearance”.xcv

The picture shows the exterior of the church following the restoration, while the map shows the extent of the grounds of the church and rectory (with the railway embankment line built in the 1870s and removed 100 years later).

The picture below shows the interior of the church following the restoration.

Closer inspection reveals that the words “HOLY HOLY HOLY” and “LORD GOD ALMIGHTY” surround the two main windows in the chancel. These are on boards, rather than painted on the stonework.

Similarly, there was wording on boards along the south wall of the nave. The mark left by the latter can still be discerned on the wall.

Barratt visited the church in 1887 and found that it stood “in a well kept churchyard, & looks as God’s acre should.” However, he felt it was “disfigured by several gas jets, which project from the top, & by a ludicrously small gilt cross, in the place of the ancient rood.”xcvi

In 1880, new heating apparatus was installed.xcvii

In the 1880s, Musters started to sell off his estate and the subsequent building programme led to a rapid growth in West Bridgford’s population – and a rise in the size of the church congregations. At the vestry meeting on 2nd May 1889, the first ever sidesmen at St Giles’ were elected: Messrs Furse and Simons.xcviii

It was soon apparent that the old parish church was unable to provide enough accommodation for the growing population. The rector of the time, Waters, responded with enthusiasm. Initially there was a proposal to have a new church building on a site facing Melton Road, However, this plan fell through and a scheme was set in motion to add another aisle to the existing church, although even then this was acknowledged to be only a short term solution. This would add seating for an additional 180 to the existing 194, at a cost of around £750. Fundraising was set in place, including a Grand Bazaar held at Trent Bridge on 9th September 1891. In a speech at the bazaar, Waters was congratulated as it was acknowledged that “there were not many clergymen who had passed eighty years of age who had undertaken to make their church as large again”.xcix

Unfortunately, Waters died in 1892, before he could see the fruit of his labours. On the Easter Sunday he had preached a “vigorous” sermon” at St Giles’ but was seized with a sudden illness on the following Wednesday and died on the Thursday evening.c Although the planned church extension was at an advanced stage – the plans of the architect, Thomas Chambers Hine, had not only been accepted but he had also been instructed to advertise for tenders – everything now came to a halt.

Aldridge became rector after Waters. Although he was only at West Bridgford for a couple of years, he continued the fund-raising activities,ci but no work was carried out on the planned extension.

When Robinson became rector in 1894, not many weeks passed before he called a meeting to address the subject of a church extension. He revisited the question of whether to extend the old church or to build a new one afresh. Once again, a preference was expressed to build afresh and a large committee was established to raise the money to build a new church which could accommodate 400 people. The proposal received the support of such people as Albert Heymann, of Bridgford Hall, who offered to serve on the committee.cii

The first number of the “West Bridgford Parish Magazine” was published in April 1895. The circulation was 425 copies.ciii

At a meeting on 14th January 1896, it was agreed that “in consideration of the probable greatly increased expenses that would be entailed by the need of a new church on the site offered by Col Davis” it would be “more advantageous to build a new church contiguous and adjoining the old church”.civ

Robinson led from the front in fund raising, offering to advance £1,500 on loan so that the building work could commence and, further, to let the rectory for a term of years, devoting the income to the building fund. By the time work started, the need for a larger church was self-evident: as well as the church itself, the large room in the Board School was used three times every Sunday and the parish church both morning and evening, with a full congregation at every service. Although extension of the parish church was the priority, it was already acknowledged that a separate church would soon be needed for the new Lady Bay Estate.cv

The sketch shows St Giles’ from the north as it was before work started on the extension, while the photograph shows the nave at the same time.

The architects’ plans for the extension included a north aisle, although that was not to be part of the immediate building project.

The foundation stone for the church extension is to be found on the east wall of the church and was laid by Lady Byron of Thrumpton Hall on Wednesday, 28 October 1896. For the ceremony, she was presented with a suitably inscribed ivory and silver trowel, which is now in the possession of the church.cvi

The stone bears the inscription: “this foundation stone was laid by the Lady Byron (Thrumpton Hall) October 28th A.D. 1896 ipc lapis adiutorii”. The latin phrase translates as “Christ, the stone of help” and echoes the inscription to be found on the south wall of the tower. In a cavity in the stone is a bottle which contains an issue of the Daily Guardian, the names of the members of the Building Committee, and of the architects, contractor, and clerk of works, together with a new shilling, sixpence, threepenny-piece, penny, and halfpenny.

The new church was going to provide substantially more accommodation. The architects estimated that they would be able to have 528 “seated with chairs in nave, south aisle and choir” or 691 “packed with chairs in nave, south aisle, space around font, in tower, but no chairs around font”.cvii

The north wall of the old church was completely removed and replaced by a large new arcade. Both the chancel arch and the rood screen were moved and placed over the entrance to the old chancel, which became home to a new organ. The gabled roof of the old chancel was replaced by an extension of the flat battlemented roof of the nave, and a new clerestory with two double windows was added. A boarded floor replaced the old stone one.cviii

The building work did not proceed without incident. In April 1898 a workman,William Henry Quayle, fell from a scaffold: he fractured his spine and eventually, in August, died of his injuries. Quayle had been ordered off the works earlier in the day for being the worse for drink, but was found at 5.30pm having fallen 13 feet to the ground.cix

A strip of land from the garden belonging to Gray of 29 Stratford Place was used to widen the road into the church yard for the building operations. This was then made permanent “to give a better approach to the churchyard for all time”.cx

The new nave and chancel were consecrated on Thursday, 15th September 1898, bringing the church’s seating capacity up to 800. The style of the new building was “decorated”, in keeping with the old church and was built and faced with Coxbench stone inside and out. The cost was around £5,700. The old church became the south aisle of the new building and it was still intended that, in due course, further work would be carried out to extend the building on the northern side. In the course of the work, the oak roof on the old church, although much decayed, was strengthened and retained. The new roofs were of pine and covered with lead.cxi In the new chancel, there were shields with the arms of York and Southwell either side of a piscina. Next was a long sedilia which could accommodate two priests, echoing the provision in the ancient chancel.

The contractor was Mr C Baines of Newark, represented by Mr Askew Browning on the works. Architects – Messrs Naylor and Sale of Derby; heating – Messrs Jerram & Co of Derby; gasfittings – Mr E Haslam of Derby; mosaic floors – Messrs Rust of London; glazing – The Lead Light Company.

There has been much praise for the extension which is in such good harmony with the original church. This is even reflected in such detail as a wooden boss in the new nave mirroring a stone carving of a green man in the old chancel.

There has been much praise for the extension which is in such good harmony with the original church. This is even reflected in such detail as a wooden boss in the new nave mirroring a stone carving of a green man in the old chancel.

St Giles’ did not confine its building enterprise to just the church extension at this time. A parish room was constructed from the rectory out-buildings and the church school was repaired and enlarged. Also, an iron mission church, to seat 200 people, was built in 1897 on a site in Pierrepont Road, given by Mt T G Mellors, to accommodate the growing population in the Lady Bay area of the parish: the opening ceremony took place on 28th March 1898.cxii

At the beginning of 1900, there was some £2,500 of debt arising from the building of the church extension. To ensure no enthusiasm was lost in paying off this sum, an anonymous donor offered £500, provided the remainder of the debt was cleared within three years.cxiii In response, a bazaar was held at the Trent Bridge Hall, styled “Ye Olde Cheshire Village Market-place”.cxiv

At the end of 1901, it was resolved to build a wooden porch inside the north entrance from Stratford Road, with a couple of doors covered with red baize.cxv

At the end of 1902, property on Stratford Road was bought from Mr Newton for £755.cxvi

In 1903, pinnacles on the tower were found to be unsafe.cxvii They were taken down and, in 1904, the rector, Richard Hargreaves, made a special appeal to parishioners for the “Tower Restoration Fund” for work which “has been thrust upon us of necessity”.cxviii The work was carried out in 1904 and included the carving of four gargoyles for the tower.cxix

By 1905, the church school had been closed as a result of competition from the Board School. However, the premises continued to be used for Sunday School and bible classes.cxx

The chapel of ease in Lady Bay, which was commenced in 1897, was completed in 1906.

In February 1908, “Ye Antient Hamelette Bazaar” was held in the Trent Bridge Hall to raise the funds needed to pay off the debt incurred in making the new approach to the parish church from Stratford Road and to reduce the mortgage on the Croft estate.cxxi The Croft estate comprises the cottages on the eastern boundary of the graveyard.

There were 619 communicants at St Giles on Easter Day in 1908.cxxii

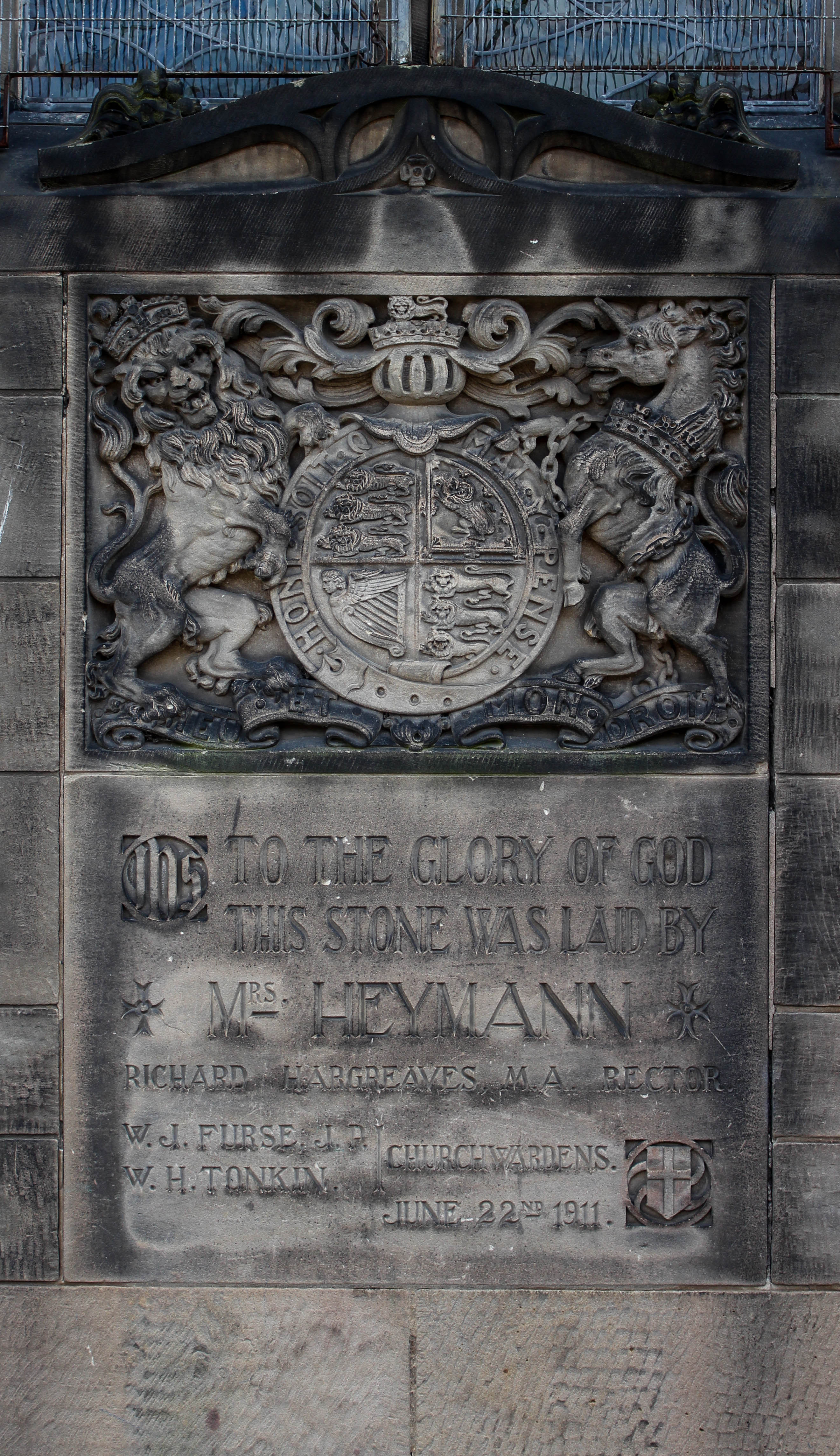

When the church was extended in 1894, it was always intended that there would be a further extension to the north and so the north wall was merely built as a temporary partition. This was to last until 1911. The foundation stone for the northern extension of the church was laid by Mrs Heymann on 22 June 1911. This was the day of the coronation of King George V and permission was sought via the Home Office, and granted, to call the aisle “The King George the Fifth’s Coronation Aisle” or “the Coronation Aisle”.cxxiii

The extension work proceeded in stages. First built was the aisle at a cost of £2,500. Then came the morning chapel, vestries and organ loft – dedicated by the Bishop of Southwell on 1st January 1913 – at a cost of £2,300. Finally there was the extension of the chancel, at a cost of £1,000.cxxiv The organ and the “stone man” found new homes in the new chapel. Much of the fitting out of the church – stained glass, wooden screens, lectern etc – was to follow in subsequent decades as memorial gifts.

The church could now accommodate 1,200. The photographs show the seating used in the new chapel and north aisle.

When the Bishop of Southwell visited in November, 1913 he reported: “I cannot refrain from congratulating the Rector of West Bridgford and his Laity upon the splendid way in which they have met the strain placed upon them by the rapid growth of this great suburb. The tiny ancient Parish Church which accommodated 120 now holds 1,250, and is always filled, whilst Lady Bay Church provides further room for 450. This is a great record, and gives encouragement to the whole district.” He considered the pressing needs of the parish to be a curate and a Parish Hall.cxxv

In June 1914, a few suffragists caused some disruption during evensong but subsequently left the building quietly.cxxvi

In 1929, a building was erected for the church on the south-west corner of the junction of Church Drive and Bridgford Road, at a cost of about £6,000. It was known as the Parochial Hall and had a large main room with a stage as well as smaller rooms, kitchen and toilets.cxxvii

The flood of May 1932 caused considerable damage to St Giles’. The wooden floors were replaced as a temporary measure and it was reported that the condition of the south chapel, which had caused anxiety in the past, demanded immediate attention.cxxviii,cxxix

The flood of May 1932 caused considerable damage to St Giles’. The wooden floors were replaced as a temporary measure and it was reported that the condition of the south chapel, which had caused anxiety in the past, demanded immediate attention.cxxviii,cxxix

The inspection after the flood also revealed that a fracture in the massive pier which carried the chancel arch, the nave arcade and the arch between the new chancel and the old, had extended and developed. There were also other fractures in the old part of the church.cxxx

Following the flood, the chancel and sanctuary of the new church were refurnished, and in 1934 the old south chancel was converted into a lady-chapel. The chancel arch and rood-screen were removed once more, and replaced as near to their original position as was permitted by the arcades of the newer central portion of the church. A stone floor again replaced the rotting boards, and the old Elizabethan communion table was cleaned and utilized as an altar for the new chapel. New screenwork, perpendicular to the old screen, was introduced. Repairs were effected to the parapets and windows, and the walls were strengthened to compensate for the disturbance of the structure identified after the flood of 1932.cxxxi

The Austrian oak screen forming the inner porch of the church was a gift of St Giles’ Lodge of freemasons “in commemoration of those brethren of the lodge who have been summoned to the Grand Lodge above”. The service of dedication of the screen, and the stained glass windows either side, was held on 29th April 1934 and was attended by nearly 400 freemasons.cxxxii

In 1936, it was announced that a site had been found for West Bridgford library. This was to be in the kitchen garden of the rectory, and area of 1,800 square yards fronting on Bridgford Road between Church Drive and Rectory Road.cxxxiii This scheme did not go ahead and the site was eventually used to build a police station.

In his paper for the Thoroton Society in 1941, Watson gave a description of the church as it was at that time.cxxxiv The predominant colour of the hangings, carpets and draperies in the church was royal blue.cxxxv

The old south aisle was furnished by the young people of the congregation in 1942.cxxxvi The aisle had been more or less unfurnished since the old pews were taken out in 1898. In addition, to the altar and associated furnishings, carved oak shields representing the ancient families who held the patronage of the church for six centuries – Lutterell, Hilton, Thimelby, Pierrepont and Musters – were placed on the roof beams. These were taken down early in the 21st century.cxxxvii

In 1944, a Church Land Fund was opened with the purpose of raising funds to build a new church to serve the housing planned for the southern end of Musters Road. A potential site was identified at the corner of Musters Road and Malvern Road which would not only be large enough for a church, vicarage and hall, but also leave space for tennis courts or other activities.cxxxviii

The church survived undamaged through the Second World War despite one night, when a shower of incendiary bombs fell around and in the churchyard.cxxxix

The flood waters of February 1946 penetrated the church and services had to be cancelled. The rector, Wilkinson, said that “the rectory garden was like a lake”. The parish clerk, Mr J H Harrison, and his wife took to the bedrooms of their cottage near the church.cxl St Giles’ was again hit by a flood in March 1947 and, for a time, the services took place in the church hall.cxli

In the 1940s, the parish bought a house for the Parish Clerk, and another for the Curate.cxlii

In 1948, the St Giles Fellowship was established and continued until the early 1980s. The picture is from the reunion on 21st June 1986.

At the service to celebrate the golden jubilee of the church extension, in September 1948, every one of the 1,200 seats in the church was filled.cxliii The service was attended by eleven former curates of the church, including Canon A H Millard who had been curate from 1895 to 1898.cxliv A list of curates from 1895 onwards, and also Parish Clerks, is printed in the booklet marking the jubilee.cxlv This was updated in the booklet for the diamond jubilee.cxlvi

All Hallows, Lady Bay was consecrated on 3rd December 1950 and became a separate parish.cxlvii The following year, a mission hall was established for the new district developed around Alford Road. A church was erected in 1957, dedicated to St Luke, and a separate parish was created in 1990. Also, in 1957, land was bought in the area of Wilford Hill; a church building was dedicated to St Paul in 1990; and a separate parish formed in 1988.

The new ring of eight bells was dedicated on 22nd March 1956. As part of the work, repairs were made to the steps of the tower and the two floors, and also to point the stonework of the battlements. The font, which was under the tower, was moved forward five feet.

A glass screen was fitted on the north side of the choir stalls, in 1957, to reduce the volume of sound from the organ.cxlviii

St Giles’ last had a verger in about 1983.cxlix

A faculty to convert the West end of the North Aisle into a small meeting room and coffee area was granted in 1984. The room was subsequently named the Biddle Lounge in memory of Walter Biddle, who was a churchwarden from 1976 to 1984.cl

St Giles’ sold 9 Wellington Crescent, the verger’s house, in about 1984.cli

To facilitate worship being led nearer to the congregation, in 1986, a faculty was granted to provide a built-up timber dais in front of the chancel area. The following year, permission was granted to provide an altar rail – made in five sections of wrought iron, finished in black lacquer, with dark oak wooden capping on each section – and an altar table 6′ x 2′ 6” x 3′ 3” in dark oak.

The new church hall was built in 1989 on land next to the north side of the church.clii (It won the new build category in the Rushcliffe Design Awards in 1993.) Also in 1989, permission was given for a footpath from the church to the new rectory built to the east of the church.

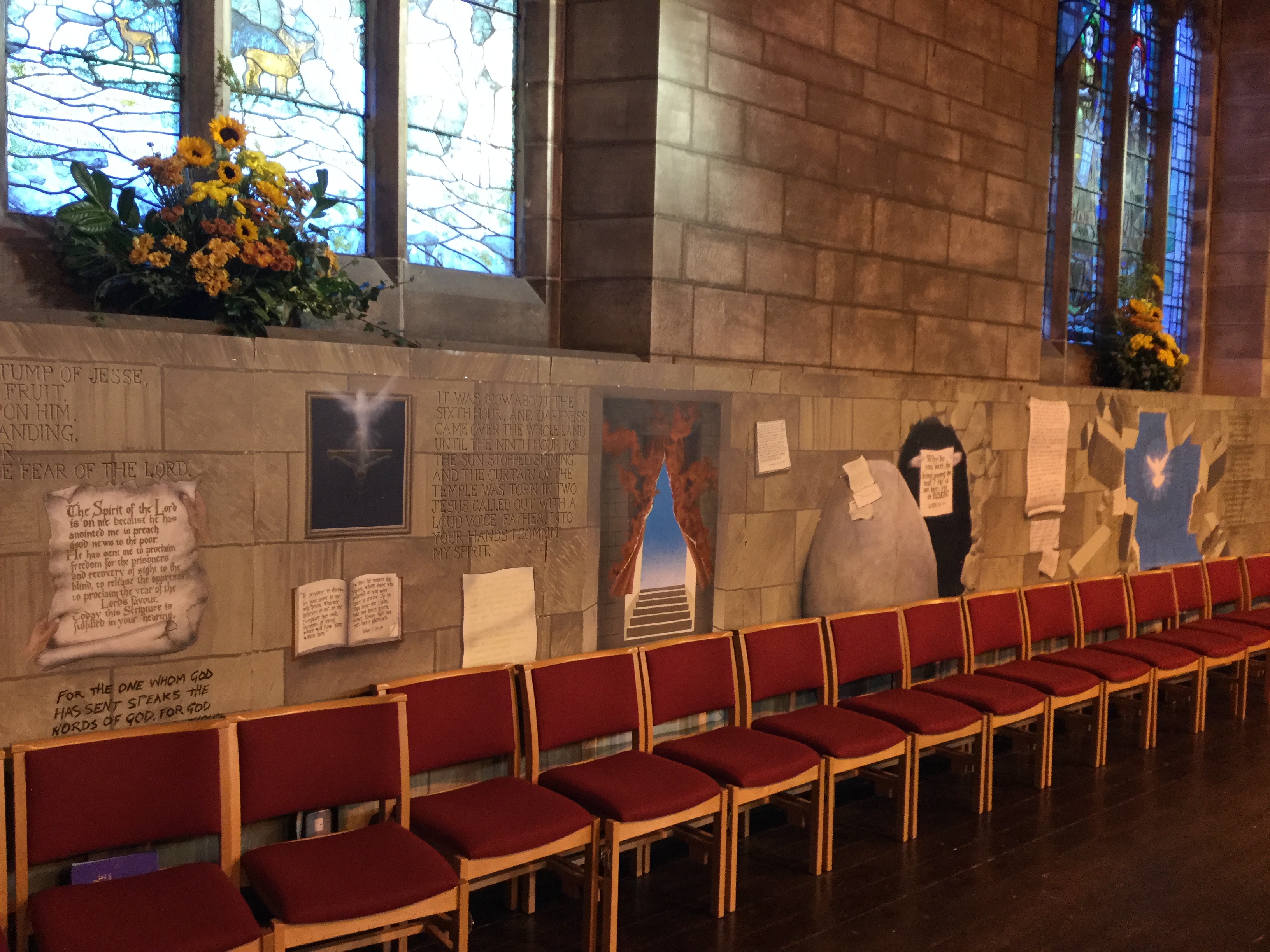

An unusual feature in St Giles’ is the artwork on boards, that are placed along the north wall of the church. These incorporate some striking tromp l’oeil effects and are by Jenny Bell, a professional artist and member of the congregation, who is also responsible for the design of two stained glass windows on the north wall. There are four sets of boards in regular use throughout the church year: the first was produced for Advent 1989, followed by another for Pentecost in 1990. Another set is based on Isaiah 52:10-12 as a call to pray for revival. There is also a fifth set, depicting lilies of the field, which was designed for times of crisis, but has only been displayed on a couple of occasions

A faculty was granted at the end of 1990 to update the South entrance to the church. The inner door of the porch was glazed, storage provided for hymn books and other items, and to conceal the area under the bell tower.

Application for a faculty for gates to protect the outer porch was made in 1992.cliii These were in memory of Ted Trew.cliv

The Biddle lounge at the West end of the church was remodelled in 2003 and named The Haven.

In 2004, the seating in the nave and north aisle was replaced with Winscombe Canticle York stacking chairs in solid beech hardwood frame with the back and seat upholstered in volcano red.

An obsolete toilet building was demolished to allow an extension to be built to the church hall in 2005. The extension is known as “The Mary Allen Room”.

References

lii Jurisdiction of the Rector of West Bridgford (c 1710) Nottingham University, Department of Manuscripts W 24